Firearms Safety Certificate

Hunter Education

Unit 1: Introduction to Hunter Education

Topic 1: Firearm Safety Rules

The Four Primary Rules of Firearm Safety (During shooting)

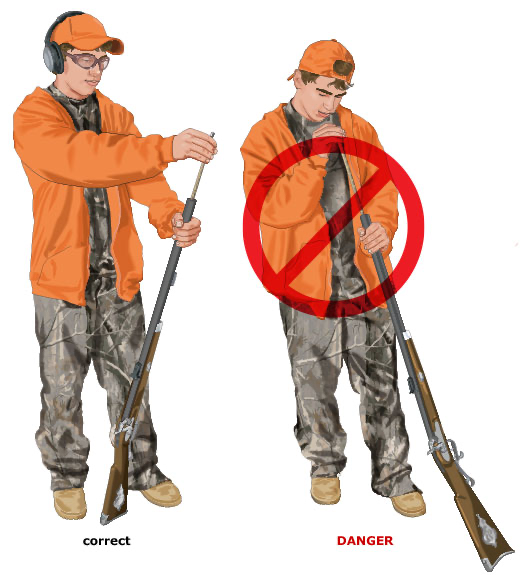

Watch that muzzle!

Keep it pointed in a safe direction at all times.Treat every firearm with the respect due a loaded gun.

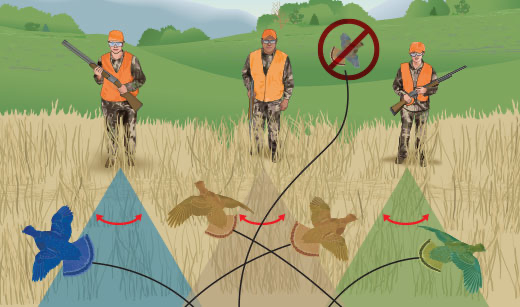

It might be, even if you think it isn’t.Be sure of the target and what is in front of it and beyond it.

Know the identifying features of the game you hunt. Make sure you have an adequate backstop—don’t shoot at a flat, hard surface or water.Keep your finger outside the trigger guard until ready to shoot.

This is the best way to prevent an accidental discharge.

Additional Rules About Firearm Safety

Check your barrel and ammunition.

Make sure the barrel and action are clear of obstructions, and carry only the proper ammunition for your gun.Unload firearms when not in use.

Leave actions open, and carry firearms in cases and unloaded to and from the shooting area.Point a firearm only at something you intend to shoot.

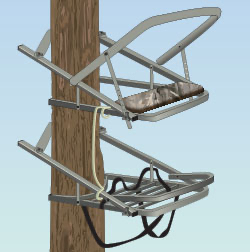

Avoid all horseplay with a gun.Don’t run, jump, or climb with a loaded firearm.

Unload a firearm before you climb a fence or tree, or jump a ditch. Pull a firearm toward you by the butt, not the muzzle.Store firearms and ammunition separately and safely.

Store each in secured locations beyond the reach of children and careless adults.Avoid alcoholic beverages before and during shooting.

Also avoid mind- or behavior-altering medicines or drugs.

Topic 2: The Importance of Hunter Education

Pittman–Robertson Act

The Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, popularly known as the Pittman–Robertson Act, was approved by Congress in 1937.

The act provides funding for the selection, restoration, and improvement of wildlife habitat and for wildlife management research. The act was amended in 1970 to include funding for hunter education programs and for the development and operation of public target ranges.

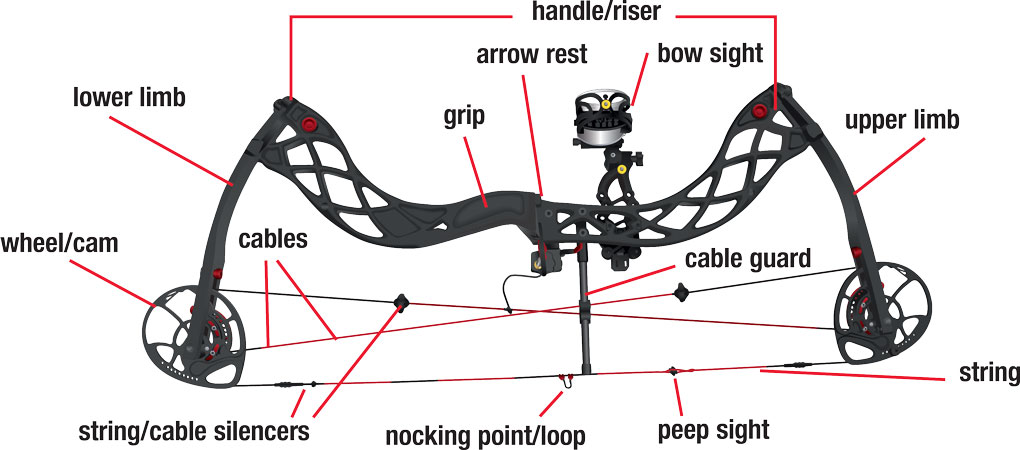

Funds for the act come from an 11% federal excise tax on sporting arms, ammunition, and archery equipment, as well as a 10% tax on handguns. One-half of the excise tax on handguns and archery equipment is used for hunter education and target ranges. These funds are collected from the manufacturers and are distributed each year to the states and territorial areas by the Department of the Interior.

Each state’s proportion of the federal funds is based on the area of the state and the number of licensed hunters in the state. The state covers the full amount of an approved project and then applies for reimbursement through federal aid for up to 75% of the project’s expenses; the state is responsible for the other 25% of the project’s cost.

Non-hunting nature lovers equally benefit from this funding since it supports the management of wildlife areas and wetlands as well as game and non-game wildlife.

“Robertson’s 29 words” are a clause in the act’s language to prevent states from diverting license fees paid by hunters away from their intended purpose: “… And which shall include a prohibition against the diversion of license fees paid by hunters for any other purpose than the administration of said State fish and game department….”

Responsibility, Safety Skills, Knowledge, and Involvement

Hunter education strives to instill responsibility, improve skills and knowledge, and encourage the involvement of beginner and veteran hunters. Responsible, ethical behavior and personal involvement are both essential to the survival of hunting.

Responsibility

A knowledgeable and skillful student of hunting will never be a true hunter unless he or she also behaves responsibly. Responsible behavior includes courtesy, respect of others and of wildlife, and involvement. Responsible hunters do not poach or act carelessly. Responsible hunters obey hunting laws, hunt fairly, practice safety rules, and wait for a clean kill before shooting. How you behave and how other people see you will determine hunting’s future.

Safety Skills

Hunting-related safety skills are gained through hands-on training and practice. It is most valuable to learn these skills from an experienced hunter.

Knowledge

Knowledge is learning and understanding the basics of safe gun handling and hunting. Before being trained in the skill of firearm shooting, you should know how the firearm operates and how to handle it safely.

Involvement

Part of the process of becoming a true, responsible sportsman is becoming involved in efforts to keep hunting a respected sport. That includes teaching others, working with landowners, and cooperating with game wardens. It also includes joining conservation organizations, which will help preserve habitat and promote wildlife management.

Unit 2: Know Your Firearm Equipment

Topic 1: What is a Firearm?

Defining a Firearm

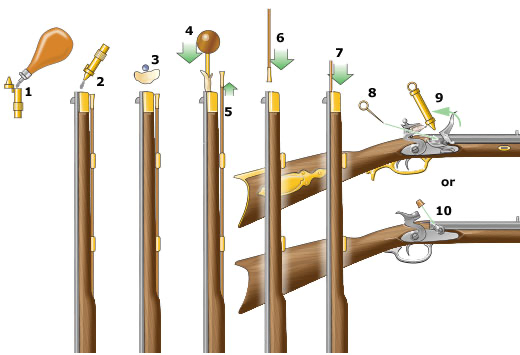

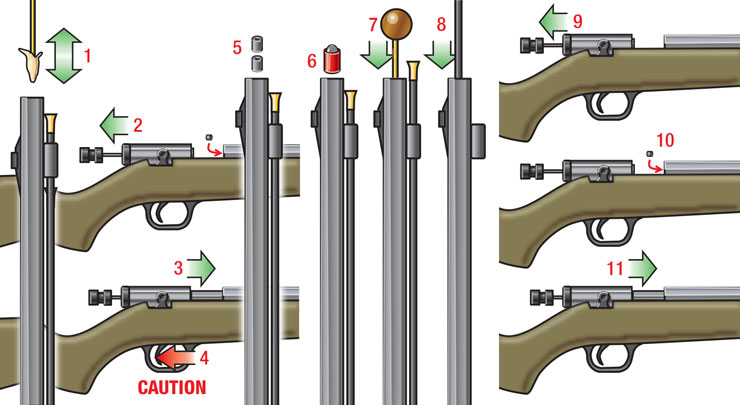

A firearm is a mechanical device that uses pressure from a burning powder to force a projectile through and out of a metal tube. To appreciate fully the importance of firearm safety, you first must understand how firearms work. This includes knowing the parts of the firearm, the types of ammunition, how ammunition is fired, and the ranges of the various firearms used for hunting.

Basic Parts of a Firearm

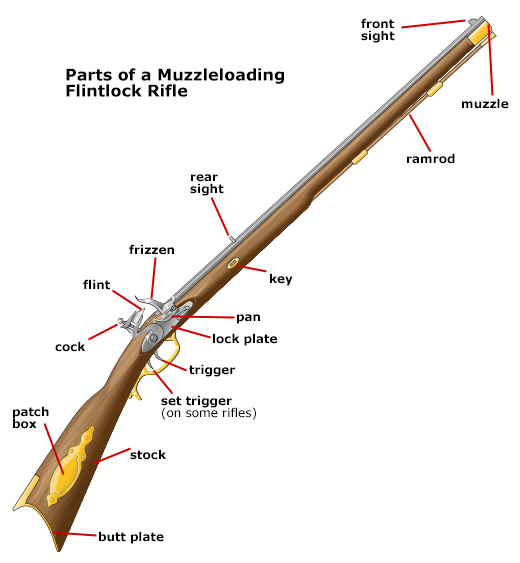

Although firearms have changed a great deal since they were first invented, the terms used for their parts have changed very little. All modern firearms have three basic groups of parts: action, stock, and barrel.

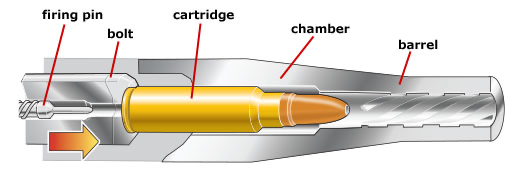

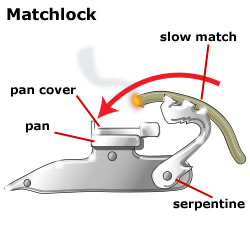

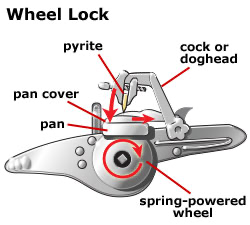

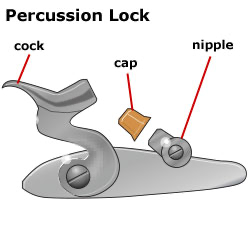

Action: The action is the heart of the firearm—the moving parts that load and fire the ammunition and eject the shells or cartridges. Several types of actions are used in modern firearms. Muzzleloaders have locks instead of actions.

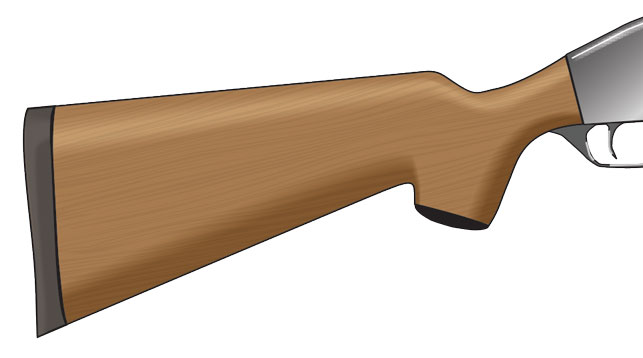

Stock: The stock is the part of the firearm that is held by the shooter. The stock also serves as the platform for supporting the action and the barrel.

Barrel: The barrel is the metal tube that the projectile travels through as a result of pressure from burning gunpowder, compressed air, or other like means. The barrel also guides the projectile in the intended direction.

Parts of a Bolt-Action Rifle

Rifles, shotguns, and handguns have many similar parts. Shown here are the parts of a commonly used rifle—a bolt-action rifle.

- Butt: The part of the stock that you hold against your shoulder when shooting

- Stock: The part of a gun which is held, or braced, against the shooter’s body

- Trigger Guard: Piece that surrounds the trigger to protect it from being squeezed or bumped accidentally

- Trigger: Small lever that is squeezed to start the firing process

- Safety: Mechanical device that blocks the trigger or hammer to help prevent accidental firing

- Bolt Handle: Handle used to open a bolt action

- Bolt: Movable metal block that seals a cartridge into the chamber on some actions

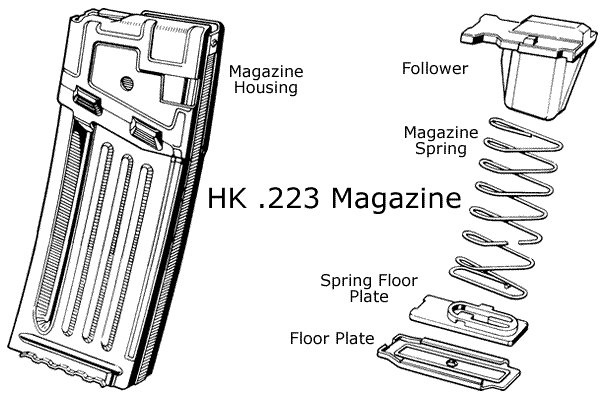

- Magazine: Container on a repeating firearm that holds ammunition before it’s loaded into the chamber; usually tubes or boxes attached to the receiver

- Chamber: Base of the barrel used to hold the cartridge or shotshell ready for shooting

- Forestock: Front portion of the stock extending under the barrel in front of the receiver; usually held by the non-trigger hand to help support the firearm

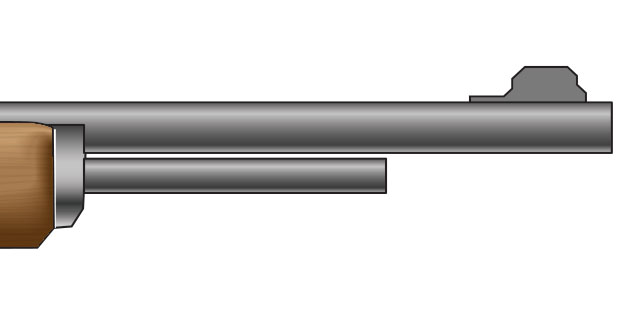

- Barrel: Metal tube through which the projectile travels

- Sight: Device used for aiming by aligning a front and rear sight

- Muzzle: The end of the barrel through which the projectile (bullet or shot) exits

Other Firearm Parts

- bore: Inside of the firearm barrel through which the projectile travels when fired

- breech: Rear end of the barrel

- firing pin: A pin that strikes the primer of the cartridge, causing ignition

- receiver: Metal housing for the working parts of the action

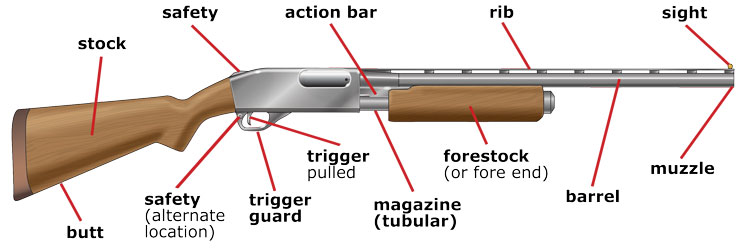

Parts of a Pump-Action Shotgun

Shotguns are another long-barreled firearm used by hunters. Below are the parts of a commonly used shotgun—the pump-action shotgun.

- Butt: The part of the stock that you hold against your shoulder when shooting

- Stock: The part of a gun which is held, or braced, against the shooter’s body

- Trigger Guard: Piece that surrounds the trigger to protect it from being squeezed or bumped accidentally

- Trigger: Small lever that is squeezed to start the firing process

- Safety: Mechanical device that blocks the trigger or hammer to help prevent accidental firing

- Safety (Alternate Position): Mechanical device that blocks the trigger or hammer to help prevent accidental firing

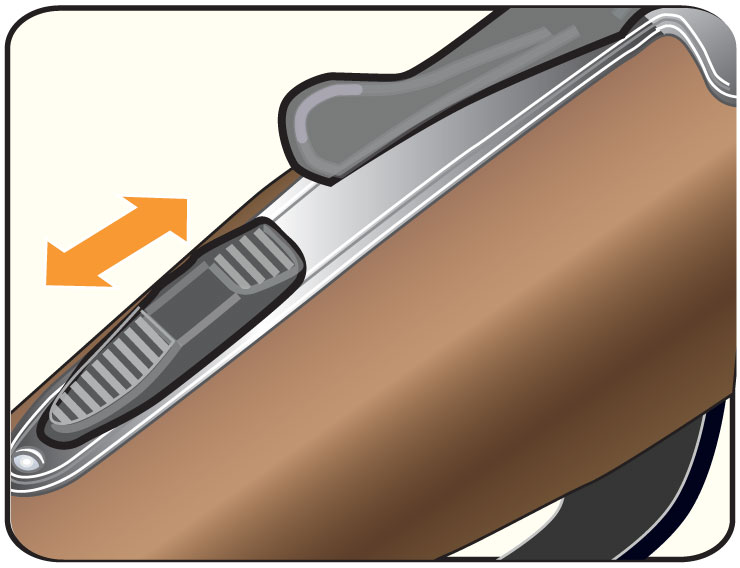

- Action Bar: Attaches the moveable forestock to the cocking/loading mechanism

- Magazine (tubular): Container on a repeating firearm that holds ammunition before it’s loaded into the chamber; usually tubes or boxes attached to the receiver

- Forestock (or fore end): On a pump (or slide) action, sliding the forestock back ejects the shotshell and cocks the action. Sliding it forward loads a fresh shell into the chamber.

- Rib: A raised surface along the top of the barrel which serves as a sighting plane

- Barrel: Metal tube through which the projectile travels

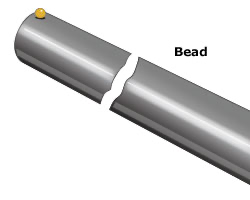

- Bead: A visual indicator for pointing the shotgun

- Muzzle: The end of the barrel through which the projectile (bullet or shot) exits

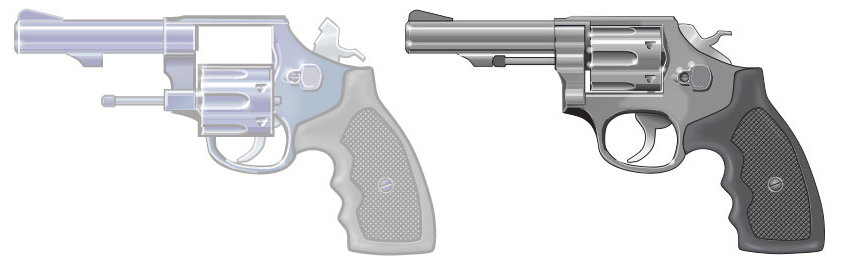

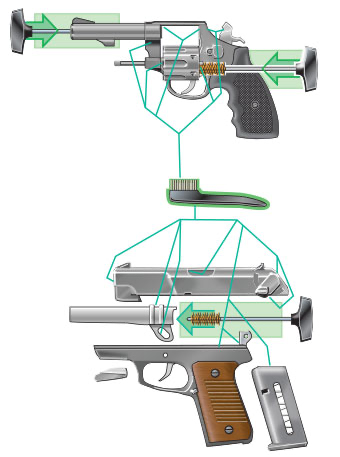

Parts of a Double-Action Revolver

Handguns (revolvers and pistols) are short-barreled firearms sometimes used for hunting. Below are the parts of a double-action revolver.

- Sight: Device used for aiming by aligning a front and rear sight

- Muzzle: The end of the barrel through which the projectile (bullet or shot) exits

- Ejector Rod: Metal rod used to help with removal of cartridges

- Cylinder: Storage for ammunition in a revolver; the cylinder rotates as the action is cocked

- Trigger Guard: Piece that surrounds the trigger to protect it from being squeezed or bumped accidentally

- Trigger: Small lever that is squeezed to start the firing process

- Hammer: Part that strikes the primer to cause ignition

- Grip: Handle of the handgun

Parts of a Semi-Automatic Pistol

Handguns (revolvers and pistols) are short-barreled firearms sometimes used for hunting. Below are the parts of a semi-automatic pistol.

- Muzzle: The end of the barrel through which the projectile (bullet or shot) exits

- Slide: Part that moves back to load cartridges

- Trigger Guard: Piece that surrounds the trigger to protect it from being squeezed or bumped accidentally

- Trigger: Small lever that is squeezed to start the firing process

- Barrel: Metal tube inside the slide through which the projectile travels

- Sight: Device used for aiming by aligning a front and rear sight

- Hammer: Part that strikes the primer to cause ignition

- Grip: Handle of the handgun

- Magazine: Detachable container on a repeating firearm that holds ammunition before it is loaded into the chamber.

Topic 2: What is Ammunition?

Defining Ammunition

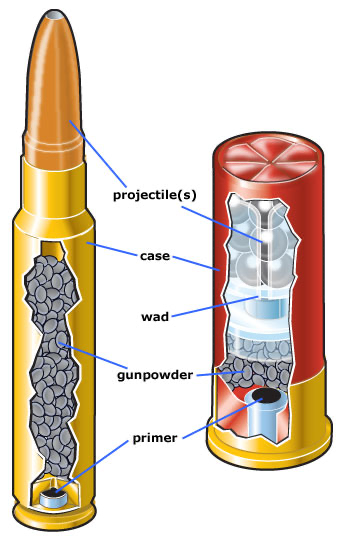

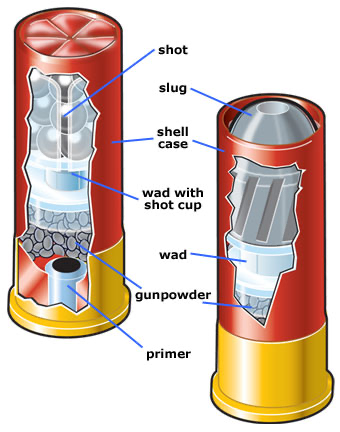

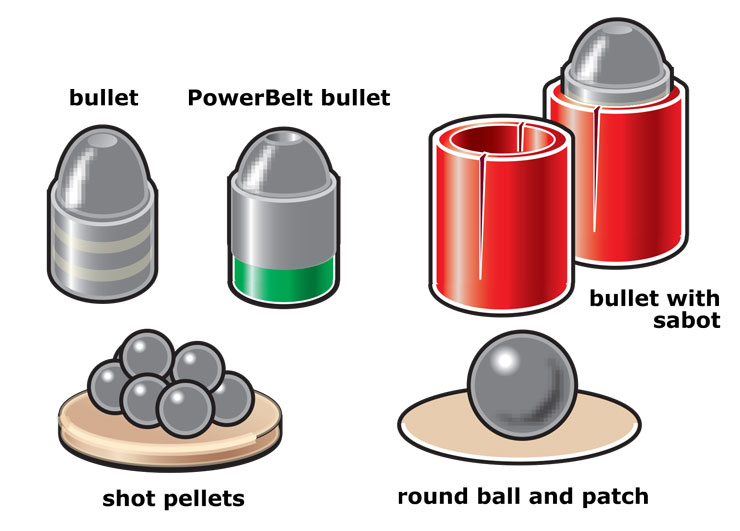

Modern ammunition varies depending on the type of firearm. Rifles and handguns use a cartridge containing a single projectile (bullet). Shotguns use a shotshell containing either a single slug or a large number of small projectiles (shot or pellets). However, the basic components of cartridges and shotshells are similar.

- cartridge: Ammunition used in modern rifles and handguns; a case containing primer, gunpowder, and a bullet

- shotshell: Ammunition used in modern shotguns; a case containing primer, gunpowder, wad, and a slug or shot

Basic Components of Ammunition

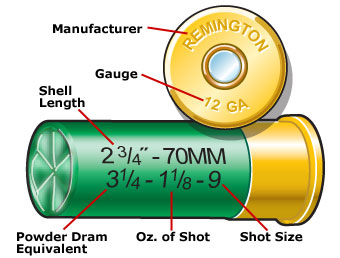

The basic components of ammunition are the case, primer, powder, and projectile(s). Shotshells have an additional component called wad.

- case: The container that holds all the other ammunition components together. It’s usually made of brass, steel, copper, paper, or plastic.

- gunpowder: A chemical mixture that burns rapidly and converts to an expanding gas when ignited. Modern smokeless powder will burn slowly when ignited in the open (outside of the case). Black powder is less stable and can be explosive when impacted or ignited in the open.

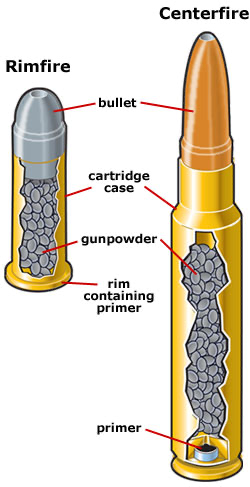

- primer: An explosive chemical compound that ignites the gunpowder when struck by a firing pin. Primer may be placed either in the rim of the case (rimfire) or in the center of the base of the case (centerfire).

- projectile: The object(s) expelled from the barrel. A bullet is a projectile, usually containing lead, fired through a rifle or handgun barrel. A slug is a solid projectile, usually of lead, fired through a shotgun barrel. Shot is a group of lead, steel, tungsten alloy, or bismuth pellets fired through a shotgun barrel.

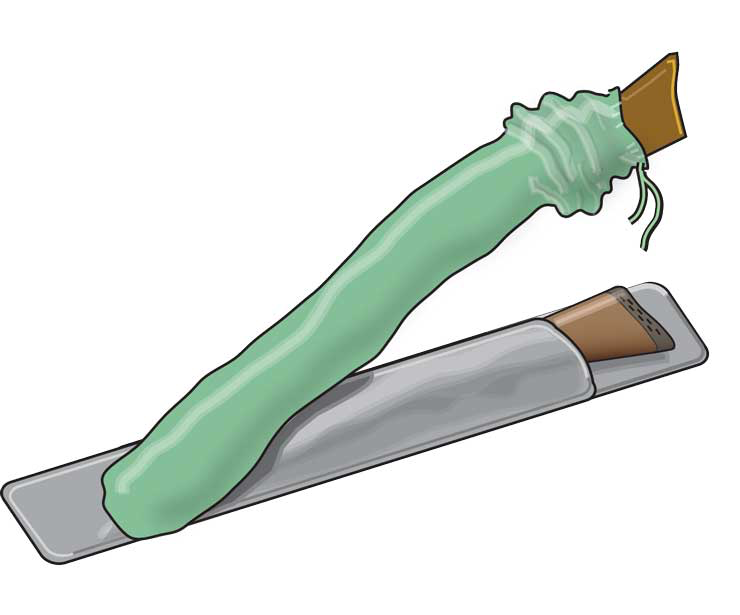

- wad: A seal and/or shot container made of paper or plastic separating the powder from the slug or shot in a shotshell. The wad prevents gas from escaping through the shot and holds the shot together as it passes through the barrel.

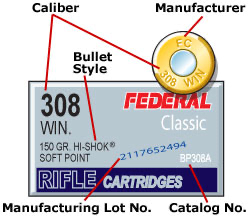

Selecting the Correct Ammunition

The way a projectile performs when shot from a firearm depends on the bullet weight or shot size, the design of the projectile, the materials used to manufacture the projectile, and the type and amount of gunpowder. When selecting the ammunition for your firearm, remember the following.

It is critical that you use the correct cartridge or shotshell for your rifle, handgun, or shotgun.

You should also consider the species being hunted, the hunting environment, and the hunting regulations.

Rifle and Handgun Cartridges

Bullets used in rifle and handgun cartridges come in various designs, sizes, and weights.

- It’s critical to select the correct cartridge for your rifle or handgun. Carefully compare the barrel stamp on the firearm against the description on the ammunition box and the stamp on each cartridge.

- The bullet usually is made of lead and may have a jacket made of copper, brass, or another metal.

- Bullets used for hunting game may have soft or hollow points designed to expand (mushroom) upon impact.

- Bullets used for target shooting usually have solid points that make smaller holes.

Common Types of Rifle Bullets

- Pointed Soft Point: High velocity, accurate bullets with a flat travel path (trajectory); excellent mushrooming

- Rounded Soft Point: Popular for low-velocity calibers; recommended for tubular magazines

- Protected Tip: Highly accurate with excellent expansion

- Full Metal Jacket: Maximum penetration without mushrooming; these bullets are illegal for big game hunting in most states

Common Types of Handgun Bullets

- Roundnose Lead: Good penetration, little expansion

- Full Metal Jacket: High penetration, no expansion

- Semi-Wad Cutter: Balances penetration and expansion

- Hollowpoint: Designed for high expansion on impact

- Wad Cutter: Flat-ended, used for target shooting; creates clean hole in paper

Hunter’s Tip

In tubular magazines, the bullet tip of one cartridge rests directly on the primer of the cartridge immediately ahead. For this reason, use only rounded or blunt tips in tubular magazines.

Centerfire and Rimfire Ammunition

Ammunition can be centerfire or rimfire.

- Centerfire ammunition is used for rifles, shotguns, and handguns. In this type of ammunition, the primer is located in the center of the casing base. Most centerfire ammunition is reloadable.

- Rimfire ammunition has the primer contained in the rim of the ammunition casing. Rimfire ammunition is limited to low-pressure loads. Rimfire cartridges are not reloadable.

Shotshells

Shotgun shells (shotshells) use different projectiles and come in different sizes.

- Shotshells use a slug or shot as the projectile(s).

- A slug is a solid projectile, usually of lead, used for hunting big game with a shotgun.

- Shot are multiple pellets fired through a shotgun barrel. Shot size is adaptable to the game being hunted. This type of projectile is used typically to hunt game birds and small game animals.

- The shotshells must match exactly the gauge and shell length specified by the manufacturer. This information usually is found on the barrel of the shotgun. Shotguns may be chambered for 2½-inch, 2¾-inch, 3-inch, or 3½-inch shells. This refers to the length of the shell after it has been fired. Never load a shotshell that exceeds the approved shell length stamped on the barrel of your shotgun.

gauge: Diameter of the bore of a shotgun and the designation for the size of ammunition for different bores

Choosing the Correct Type and Size of Shot

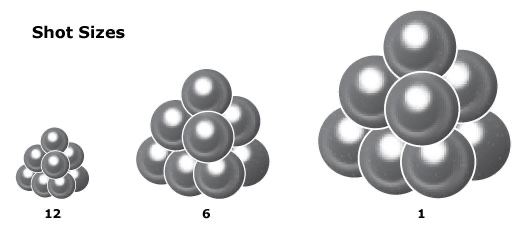

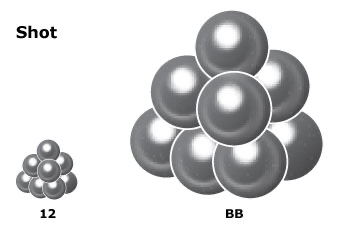

You also must choose the correct type and size of shot for the shotshell. In general, as the size of your target decreases, you should decrease the diameter of the shot you use.

- As pellet diameter decreases, more shot can be placed in a standard shotshell.

- The smaller the shot “number,” the larger the pellet diameter.

- Shotshell marked as magnum means the shell has more shot or more gunpowder than a regular shell. Magnum and regular shotshells are interchangeable if the correct gauge and shell length are used.

Steel Shot

Steel shot pellets react differently than lead when shot. Because steel shot pellets are not as dense, they weigh about one-third less than lead shot pellets of the same size. Also, steel is harder, does not deform, and is not as unstable in flight as lead. It will produce a tighter pattern than lead shot. If using steel shot for hunting, choose a steel shot size one to two sizes larger than the lead shot you would select and choose a less constrictive choke.

Shot Sizes

Shot size is adaptable to the game being hunted. As pellet diameter decreases, more shot can be placed in a standard shotshell load. The smaller the shot number, the larger the shot size.

Non-Toxic Shot

Non-toxic shot is required throughout the U.S. for waterfowl hunting. Studies showed that many waterfowl died each year because of lead poisoning. Lead pellets from traditional shotshells were picked up and digested by waterfowl. The toxic effect spread to other birds, such as the bald eagle, which consumed the poisoned waterfowl. To reduce this problem, conservationists worked with shotshell manufacturers to produce effective alternatives to lead shot—steel, tungsten alloy, or bismuth shot.

Topic 3: How a Firearm Works?

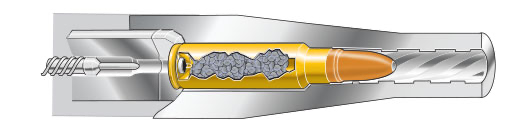

The Basic Firing Process

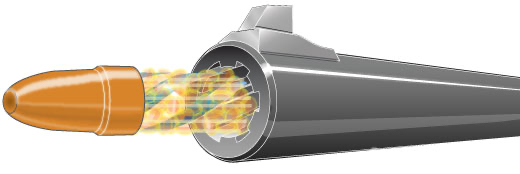

The same physical process is used to shoot shotshells from shotguns or cartridges from rifles or handguns. Pulling the trigger causes the firing pin to strike and explode the primer in the base of the cartridge or shotshell. The spark from the primer ignites the gunpowder, which burns rapidly and converts to a gas. The gas rapidly expands and drives the projectile(s) through the barrel with great force.

How the Rifle and Handgun Fire

A cartridge is inserted into the chamber.

The action is closed, and the firing pin is pushed back and held back under spring tension.

The trigger is squeezed, releasing the firing pin, which moves forward with great force. The firing pin strikes the primer, causing it to explode.

The spark from the primer ignites the gunpowder. Gas converted from the burning powder rapidly expands in the cartridge. The expanding gas forces the bullet out of the cartridge and down the barrel with great speed. The rifling in the barrel causes the bullet to spin as it travels out of the barrel. The bullet’s speed and escaping gases produce a “bang.”

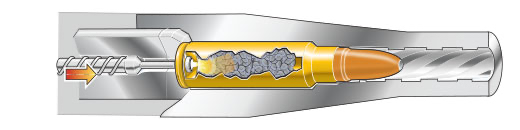

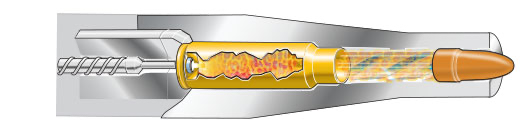

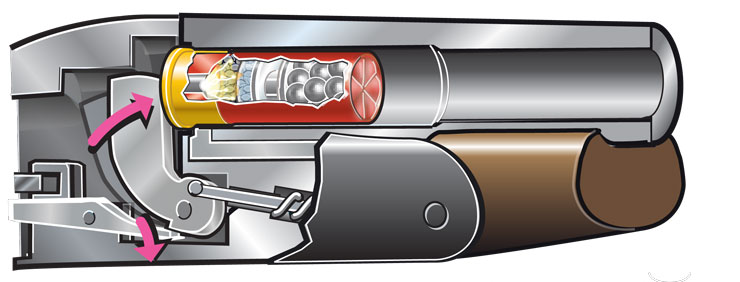

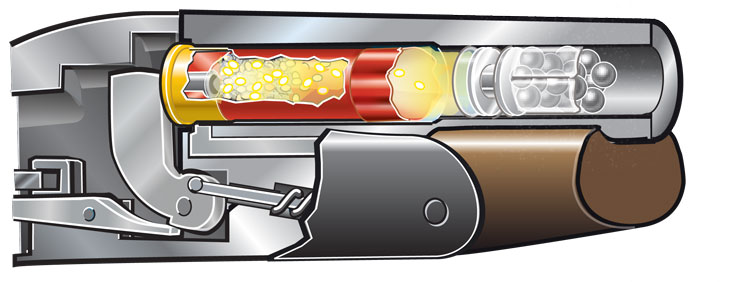

How the Shotgun Shoots

A shotshell is inserted into the chamber. Closing the action pushes the firing pin back and holds it under spring tension.

Pulling the trigger releases the firing pin. The firing pin strikes the primer producing sparks.

Heat and sparks from the primer ignite the gunpowder. Gas converted from the burning powder expands in the shell. The expanding gas forces the wad and shot out of the plastic body of the shell.

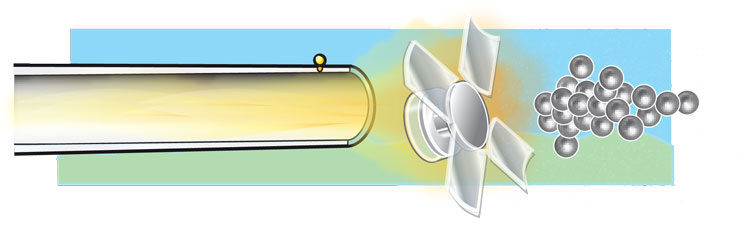

The escaping gases produce a “bang” as the wad and shot leave the barrel. The wad quickly opens and falls away. The shot cluster spreads. This spread is called the shot string.

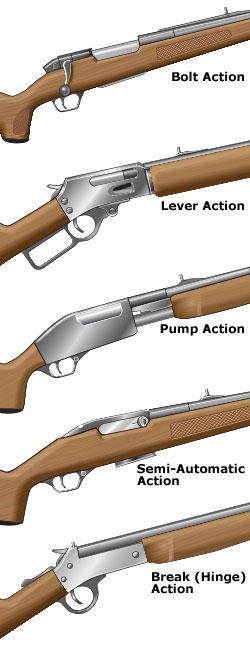

Topic 4: Common Features of Firearms: Firearm Actions

Introduction to Firearm Actions

All types of firearms have actions and sights, and they may have safeties or magazines.

Types of Actions

Firearms can be classified by their action type. The action of a firearm is made up of parts that load, unload, fire, and eject the shotshell or cartridge. Actions are either single-shot or repeating styles. Single-shot firearms must be reloaded each time the firearm is fired. Repeating firearms have extra cartridges or shotshells ready in a magazine, cylinder, or extra barrel.

Bolt Action

A bolt-action firearm operates like opening and closing a door bolt. The bolt solidly locks into the breech, making it accurate and dependable.

- To open the action, lift the handle up and pull it to the rear.

- If the firearm is loaded, the cartridge or shotshell will be ejected as you pull the bolt to the rear. To make sure it’s unloaded, open the action, and check both the chamber and the magazine for cartridges or shotshells.

- You can store a bolt-action firearm safely by storing the bolt separately from the firearm.

Lever Action

The lever-action firearm has a large metal lever located behind the trigger. This handle usually forms the trigger guard as well.

- To open the action, push the lever downward and forward, which extracts the cartridge case from the chamber and ejects it. If a magazine holds extra cartridges, another is immediately ready to be loaded into the chamber.

- It’s often difficult to tell whether a lever-action firearm is loaded. To unload, push the lever downward and forward repeatedly until no more cartridges are ejected. To make sure it’s unloaded, open the action, and check both the chamber and the magazine for cartridges.

- Most models also have an exposed hammer, which can be dangerous.

- Always use extra caution to keep your hands away from the trigger while working the lever action.

Pump Action

The pump-action firearm is fast and smooth. It allows the shooter to re-cock the firearm without taking his or her eye off the target. The pump action also is referred to as “slide action” or “trombone action.”

- To open the action, slide the forestock to the rear, which extracts the cartridge or shotshell from the chamber and ejects it. Sliding the forestock toward the muzzle closes the action and readies another cartridge or shell for loading. A pump-action firearm will open only after it’s fired or if a release lever is pressed and the forestock is pulled to the rear.

- To make sure it’s unloaded, open the action, and check both the chamber and the magazine for cartridges or shotshells.

Semi-Automatic (or Autoloading) Action

As each shot is fired manually, the case of the cartridge or shotshell is ejected automatically and the chamber is reloaded automatically.

- To open the action, you must pull back the bolt’s operating handle (on a rifle or shotgun) or the slide (on a pistol). Most semi-automatics, when the bolt or slide is pulled back, will lock in the open position if the magazine is empty. If the firearm does not lock open, it means that a cartridge or shotshell from the magazine has gone into the chamber, making the firearm ready to fire. A few semi-automatics do not lock open and must be held open to check the chamber.

- To unload, first remove the magazine, and lock the action open. Then make sure it’s unloaded—check both the chamber and the magazine for extra cartridges or shells.

- When closing the action for loading, pull back to unlock the bolt or slide and then let go, allowing it to travel forward on its own. Do not guide it forward with your hand because it may not seat properly.

- On a semi-automatic, the trigger must be pulled each time a shot is fired. This makes the semi-automatic different from the fully automatic firearm, which fires continuously as long as the trigger is held down. The fully automatic firearm may not be used for hunting or sport shooting.

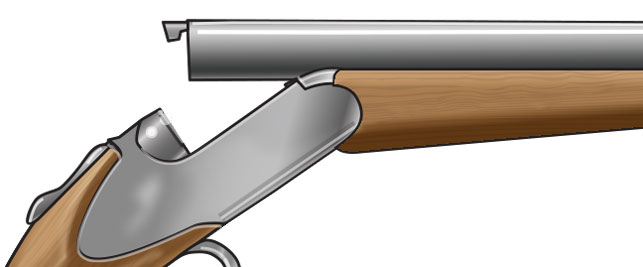

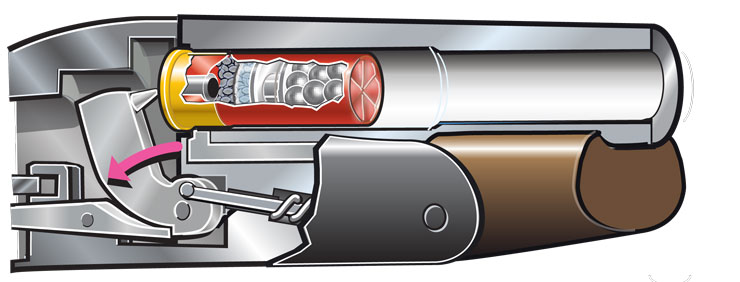

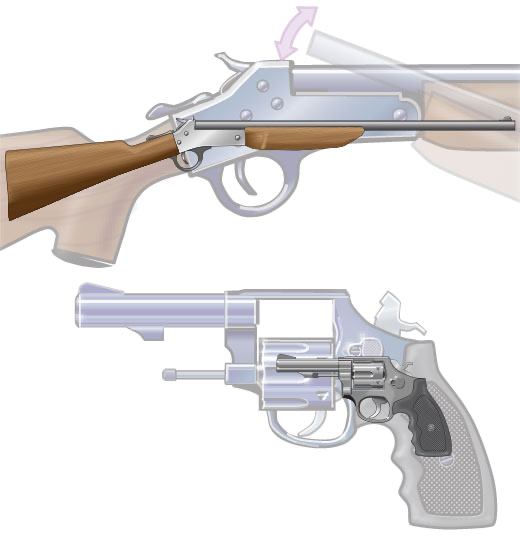

Break (or Hinge) Action

The break-action firearm operates on the same principle as a door hinge. Simple to load and unload, a hinge action is often chosen as a hunter’s first firearm.

- To open the action, point the barrel(s) at the ground. A release is pressed, and the stock drops downward. This allows the cartridges or shotshells to eject or to be removed manually if the firearm is loaded.

- Hinge-action firearms have a separate barrel for each shot rather than a magazine. Most models have one or two barrels, but some have up to four.

- Some models also have an exposed hammer(s), which can be dangerous.

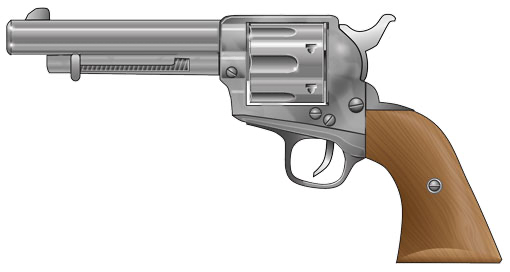

Revolving Action

The revolving action takes its name from a revolving cylinder containing a number of cartridge chambers. One chamber at a time lines up with the barrel as the firearm is fired. Revolving cylinders may rotate either clockwise or counterclockwise, depending on the manufacturer. This type of action is usually found on handguns but may be found on some older rifles. Revolving actions are referred to as either “single action” or “double action.”

- double action: Pulling the trigger both cocks and releases the hammer. A double-action revolver typically also can be hammer-cocked like a single-action revolver.

- single action: Will fire only after the hammer has been cocked manually.

Common Actions on Rifles and Shotguns

Common Actions on Rifles

Single-shot rifles are usually break- or bolt-actions. Repeating rifles include the bolt-action, lever-action, pump-action, and semi-automatic types. Operating the lever, bolt, or forestock ejects the empty cartridge case, chambers a new round of ammunition, and cocks the gun.

Common Actions on Shotguns

Shotguns use many of the same actions as rifles—the pump action, semi-automatic action, and bolt action. They also use a break action as either a single barrel or double barrels. The double barrels can be arranged horizontally (side-by-side) or vertically (over-under).

Common Actions on Handguns

Handguns fall into two basic types: revolvers (that fire from a revolving cylinder) and pistols (all other types, including auto-loading and single-shot handguns). There are two common types of actions used in sport shooting.

Single-Action Handguns

- Single-action means that the gun must be manually cocked for each shot (revolvers) or for the first shot (autoloaders), usually by pulling back the hammer or cycling the slide.

- A single-action handgun’s manual cocking allows a shorter, lighter trigger pull that is an aid to accuracy; but an accidental light touch of the trigger will usually fire a cocked single-action gun if the safety is off.

Double-Action Handguns

- Double-action means that trigger movement cocks the action as the trigger is pulled during firing, but the gun can also be manually cocked like a single-action. A gun which can be cocked only by trigger action (no manual cocking) is known by the term double-action-only.

- A double-action handgun’s trigger-cocking allows a faster shot, since no separate manual cocking is needed. A double-action gun’s longer, heavier trigger pull is also considered safer. In fact, many double-action guns, especially revolvers, have no mechanical safety at all, since only a long, deliberate pull will fire the handgun.

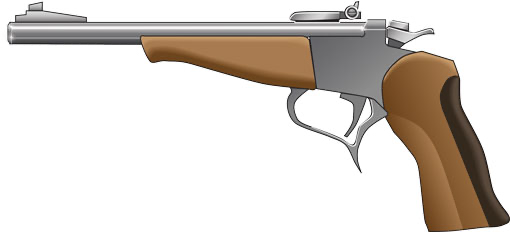

Single-Shot Pistol (Break-Action)

Single-Action Revolver

Double-Action Revolver

Semi-Automatic Pistol

Topic 4: Common Features of Firearms: Firearm Safeties

Safety Mechanisms

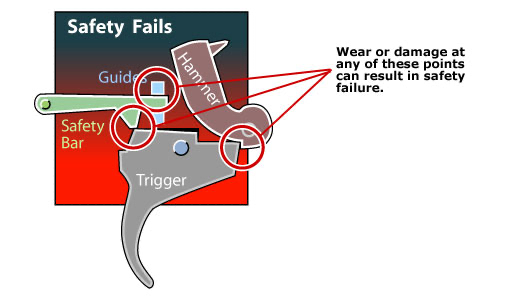

A safety is a device that blocks the action to prevent the firearm from shooting until the safety is released or pushed to the off position. The safety is intended to prevent the firearm from being fired accidentally. However, safeties should never be relied on totally to protect against accidental shooting. Safeties are mechanical devices subject to mechanical failure from wear and other factors, and they can fail when least expected. Also, safeties can be unknowingly bumped from the safe position as your firearm is being handled or as it catches on clothing or tree branches.

How Safeties Can Fail

A safety is only a backup to safe gunhandling habits.

Typical Locations of Safeties

All safeties are located around the receiver of the firearm and are usually easy to spot. The orange outlines indicate where safeties typically are located on rifles, shotguns, and handguns.

Types of Safeties

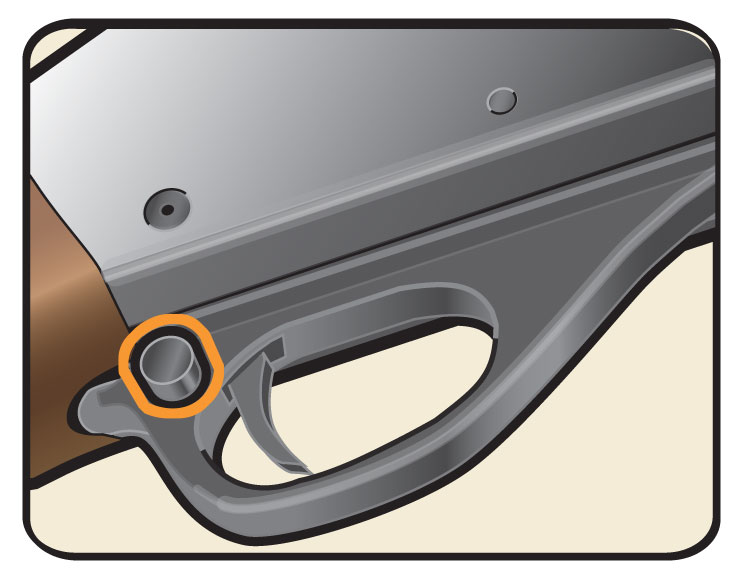

Cross-Bolt Safety

- Common on pump and semi-automatic firearms

- A simple, push-button action that blocks the trigger or hammer

- Usually located at the trigger guard or ahead of the hammer

Cross-Bolt Trigger Safety on the Trigger Guard of a Pump-Action Shotgun

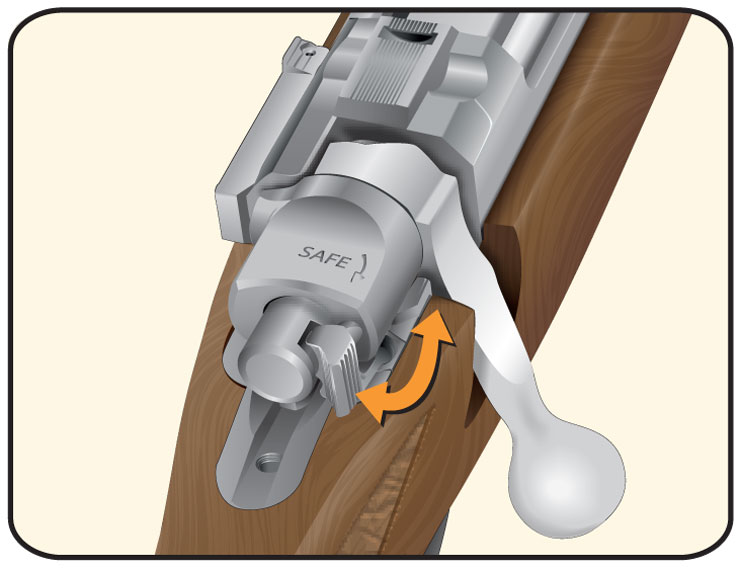

Pivot Safety

- Common on bolt-action rifles and found on some semi-automatic pistols

- A pivoting lever or tab that blocks the trigger or firing pin

- Located on the frame (blocks trigger) or on the bolt or slide (blocks firing pin)

Pivot Safety on the Bolt of a Bolt-Action Rifle

Pivot Safety on the Slide of a Semi-Automatic Handgun

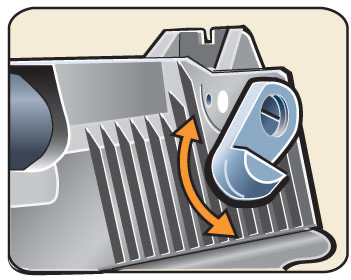

Slide or Tang Safety

- Common on some rifles and break-action shotguns

- A sliding bar or button that blocks the firing action

- Located on the tang (a metal strip behind the receiver) of break-action firearms or on the side of the receiver on some rifles

Slide Safety on the Tang of a Break-Action Shotgun

Half-Cock or Hammer Safety

- Common on single-action revolvers and other firearms with exposed hammers

- Positions the hammer at half-cock, away from the firing pin

- Engaged by placing the hammer at half-cock

- While not a true safety, it is sometimes described as a mechanical safety device by firearm manufacturers

Safeties Don’t Replace Safe Handling

- You should never replace safe firearm handling with trusting the safety on a firearm. A safety is a mechanical device that could fail. Don’t release the safety until just before you shoot.

- Knowing where the safety is and how it works is not always as simple as it might seem. There are many types of safeties. Sometimes people alter or modify their guns to disable the safety. This is very dangerous, especially if the gun gets into the hands of an inexperienced shooter. Be sure you know how the safety works on your own gun or any others you handle. Never alter or modify your firearm yourself. Have an experienced gunsmith look at your gun if the safety does not work or if anything else is wrong with it.

Topic 6: Common Features of Firearms: Magazines and Sights

Magazines

In repeating firearms, the magazine is the place that stores the ammunition that has not been fired. It is a removable, spring-powered ammunition storage and feeding device that is inserted into a semi-automatic firearm. When you work the action, a cartridge is picked up from the magazine and placed in the chamber ready to be fired.

- Magazines are designed with a spring and follower, which push against the cartridges to move them into the action. When checking a magazine to make sure it’s empty, you must be able to either see or feel the follower; if you cannot see or feel the follower, there may be a cartridge jammed in the magazine, which can be dangerous. Tubular magazines require close attention to make sure a cartridge is not jammed in the magazine.

- Magazines may be detachable or fixed.

- Detachable magazines allow you to remove extra ammunition from the firearm by simply removing the magazine.

- Fixed magazines require the ammunition to be removed manually from the gun itself. These include tubular, hinged-floor-plate, and revolving magazines.

Introduction to Sights

A sight is a device used to line up the muzzle with the shooter’s eye so that he or she can hit the target. Sights are more critical on a firearm that fires a single projectile (rifle and handgun) than on a firearm that shoots a pattern of shot (shotgun). Shotguns usually have a simple pointing bead. Rifles typically have an open, aperture (peep), or telescopic sight. Most handguns have an iron (open) sight, although some specialized handguns have a dot, a laser, or a telescopic sight.

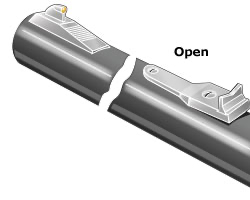

Sights: Bead and Open

Bead Sight: Simple round bead set into the top of the barrel near the muzzle of a shotgun. Some shotguns have a second, smaller bead about halfway back on the barrel. The shooter uses the shotgun to “point” at and follow a moving object. The bead is used only for a reference as the shotgun is pointed and moved to follow flying or running targets.

Open (Iron) Sight: Combination of a bead or post front sight and a notched rear sight. These sights are simple and inexpensive. Open sights allow quick sighting. To aim, you center the top of the bead or post within the notch of the rear sight, and line up on the target. Open sights can be fixed or adjustable.

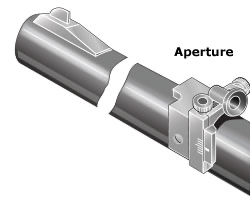

Sights: Aperture (Peep)

Aperture (Peep) Sight: Combination of a bead or post front sight and a round hole set on the rifle’s receiver close to the shooter’s eye. To aim, you center the target in the rear peep or aperture sight, and then bring the front sight into the center of the hole. An aperture sight lets you aim more accurately and is adjusted more easily than an open sight.

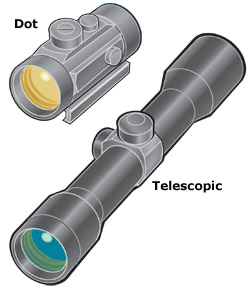

Sights: Telescopic (Scope) and Dot

Telescopic Sight (Scope): Small telescope mounted on your firearm. A scope gathers light to brighten the image, uses mirrors and lenses to magnify the target, and does away with aligning rear and front sights. The aiming device inside the scope is called the “reticle.” To aim, you simply look through the scope, and line up the crosshairs, post, or dot with your target. Telescopic sights provide the most accurate aiming, which makes them popular for hunting.

Dot Sight: Small device mounted on your firearm. A dot sight uses electronics or optical fibers to project a glowing dot or other mark on a lens in front of the shooter’s eye. Some dot sights also magnify like telescopic sights.

Topic 7: Difference Between Firearms

Differences Between Rifles, Shotguns, and Handguns

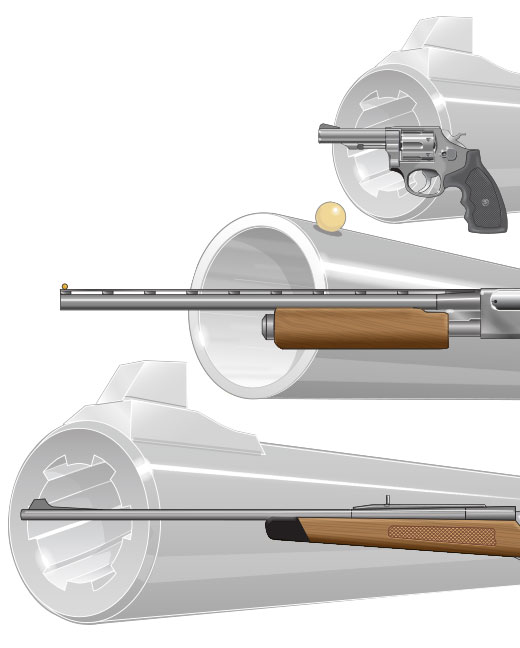

The main differences between rifles, shotguns, and handguns are their barrels, their intended targets, and the type of ammunition used.

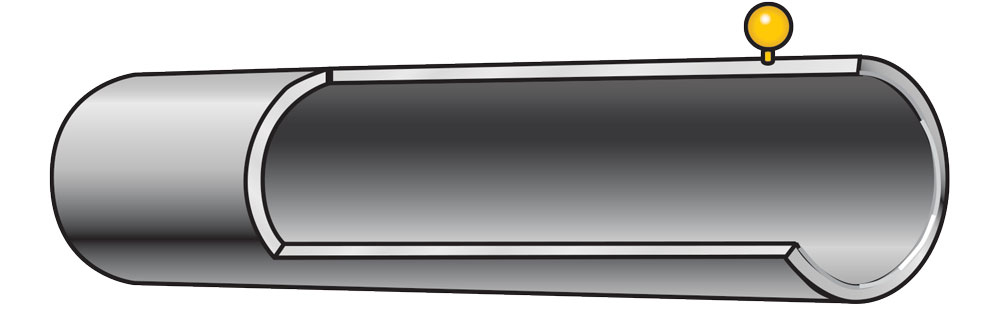

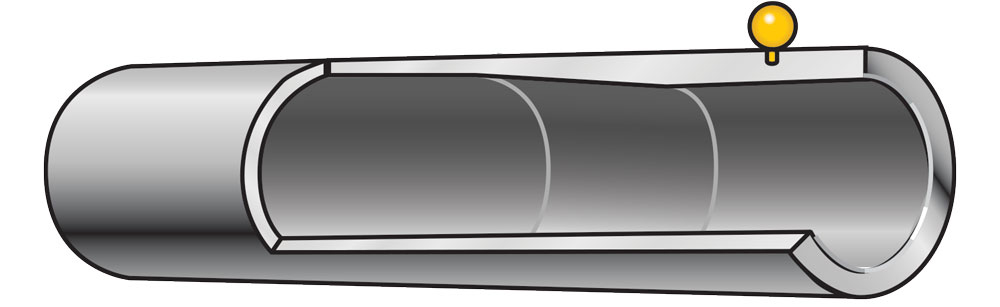

- Rifle

- The rifle has a long barrel with rifling and thick walls to withstand high pressures. Rifling puts a spiral spin on a bullet fired from a rifle, increasing accuracy and distance.

- Rifles are typically used for firing at stationary targets.

- The bore of a rifle barrel is made for only one specific caliber of ammunition.

- Shotgun

- The shotgun has a long barrel and usually has a smooth bore to reduce friction. The barrel’s walls are thinner due to reduced pressures. If a shotgun is designed to fire slugs, it might have a rifled barrel.

- Shotguns are typically used for shooting at moving targets in the air.

- The bore of a shotgun barrel is made for only one specific gauge of ammunition.

- Handgun

- The handgun has a short barrel with rifling and thick walls to withstand high pressures. Because of the short barrel, extra care must be taken to control the muzzle of a handgun. Like the rifle, rifling in the handgun puts a spiral spin on a bullet when fired, increasing accuracy and distance.

- Handguns are typically used for firing at stationary targets.

- The bore of a handgun barrel is usually made for only one specific caliber of ammunition.

- caliber: Diameter of the bore of a rifle or handgun as measured from land to opposite land on rifled barrels and the designation for the size of ammunition for different bores

- rifling: Spiral grooves cut into the bore of a firearm barrel together with the lands—the ridges of metal between the grooves; rifling makes a bullet spin in flight, increasing accuracy and distance

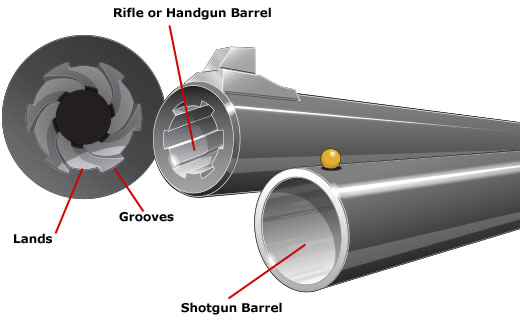

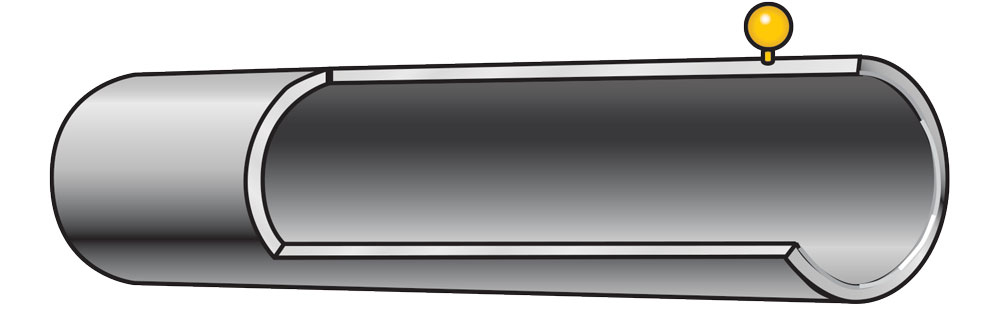

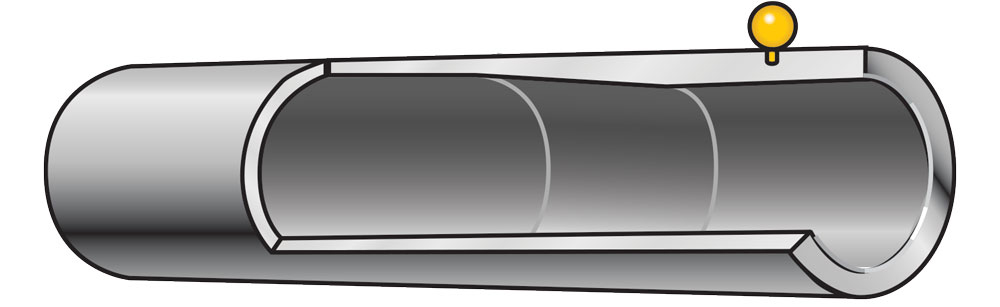

Rifling in the Rifle or Handgun Bore

The bore of a rifle or handgun is grooved, which puts a spiral spin on the bullet for greater accuracy. The bore of the shotgun barrel is smooth because rifling would spread the shot pattern too soon.

- grooves: The spiral cuts in a rifled bore

- lands: The ridges of metal between the grooves in a rifled bore

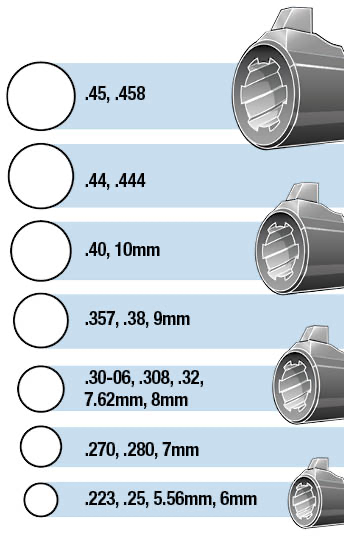

A Rifle’s or Handgun’s Caliber

Caliber is used to describe the size of a rifle or handgun bore and the size of cartridges designed for different bores.

- Caliber usually is measured as the diameter of the bore from land to opposite land and is expressed in hundredths of an inch, thousandths of an inch, or millimeters. For example, a .270-caliber rifle bore measures 270/1000ths of an inch in diameter between the lands and has a larger bore diameter than a .223-caliber rifle. However, there is no standard established for designating caliber. In some cases, the caliber is given as the diameter of the bullet, which is the distance between the grooves.

- Caliber designations sometimes have a second number that has nothing to do with the diameter. For example, the popular .30-30 is a .30-caliber cartridge, but the second number is a holdover from the days when the cartridge took 30 grains of powder. The “06” in .30-06 refers to the year (1906) it became the official ammunition of the U.S. military.

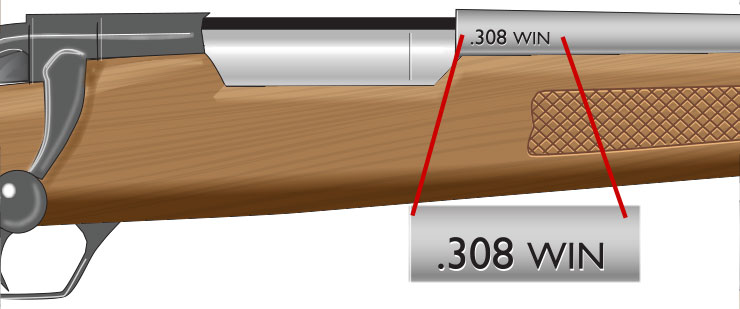

- Every rifle or handgun is designed for a specific cartridge. The ammunition must match the barrel stamp on the firearm.

- Having the same bore size does not mean different cartridges are interchangeable. For example, there are several .30-caliber firearms that use the same bullet size but are designed for different cartridges (the .30-30, .30-06, .308, and the .300 Savage). If you cannot find the caliber stamped on the firearm, take it to a qualified gunsmith.

The circles show bore sizes of common calibers.

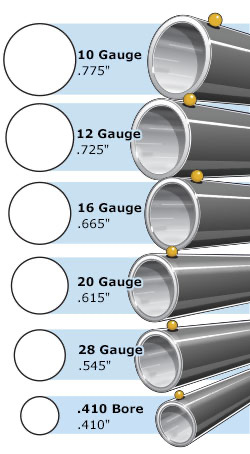

A Shotgun’s Gauge

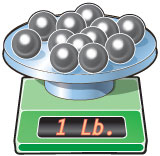

Shotguns are classified by gauge, which is a measure related to the diameter of the smooth shotgun bore and the size of the shotshell designed for that bore.

- Common shotgun gauges are 10-gauge, 12-gauge, 16-gauge, 20-gauge, and 28-gauge. The smaller the gauge number, the larger the shotgun bore. Gauge is determined by the number of lead balls of size equal to the approximate diameter of the bore that it takes to weigh one pound. For example, it would take 12 lead balls with the same diameter as a 12-gauge shotgun bore to weigh one pound. Today, however, gauge can be measured much the same way as caliber, by measuring the inside bore diameter.

- The .410-bore shotgun is the only exception to the gauge designation for shotguns. It has an actual bore diameter of 410/1000ths of an inch, which is approximately equivalent to a 67½ gauge.

- Each gauge of shotgun shoots only shells of the same gauge. For example, 12-gauge guns use only 12-gauge shells.

- The gauge of a shotgun is usually marked on the rear of the barrel, and the gauge of a shell is marked on the shell as well as on the factory box.

Sizes shown are the minimum inside bore diameter with a tolerance of +0.020”. Data is presented courtesy of SAAMI.

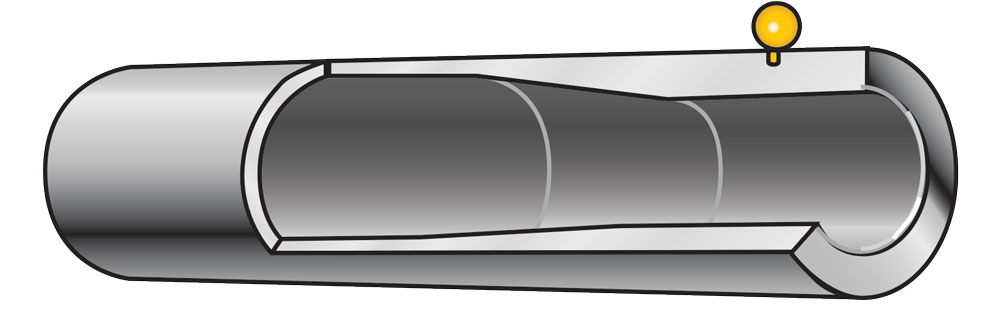

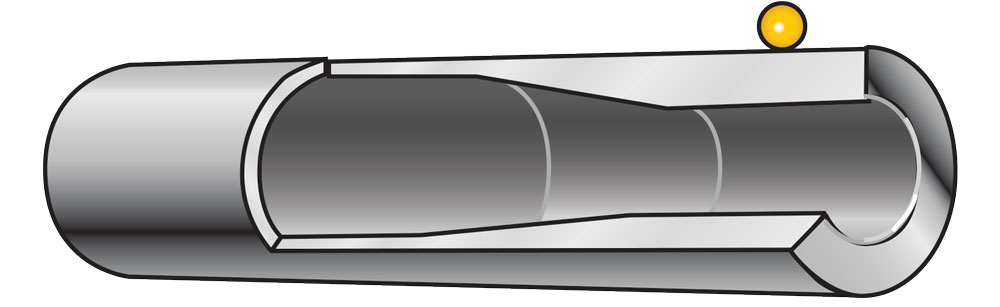

Shotgun Choke and Shot String

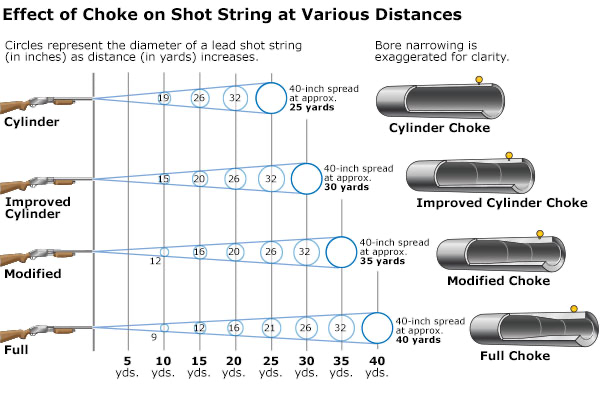

When a shotshell is fired from a shotgun, the pellets leave the barrel and begin to spread or scatter. The farther the pellets travel, the greater the spread of the group of pellets (shot) both in length and diameter. This spread is called the shot string. To control the shot string, shotgun barrels have a choke that will affect the shot pattern when the shot string hits the target.

- choke: The degree of narrowing at the muzzle end of the shotgun barrel

- shot pattern: The spread of shot pellets after they hit a non-moving target

- shot string: The three-dimensional spread of shot pellets after they leave the barrel

Types of Chokes

Your distance from the target determines the choke you need. The choke of a shotgun determines shot string only. It has no bearing on shot speed (velocity) or distance (range). That is, the choke does not alter the shotgun’s power—it just controls how tight or spread out the pellets will be at a specific distance.

Cylinder choke is an unconstricted barrel. The shot string spreads quickly.

Cylinder Choke

Improved Cylinder choke has a slight constriction. It allows the shot string to spread fairly quickly. This is a good choice for quail, rabbits, and other upland game at relatively close ranges.

Improved Cylinder Choke

Modified choke has moderate constriction. The pellets stay together longer, making the shot string denser and more useful at longer ranges. This choke is used often when dove hunting and when using steel shot to hunt for ducks or geese. There is also an Improved Modified choke that is slightly tighter than Modified.

Modified Choke

Full choke has tight constriction. The shot holds together even longer, making this choke good for squirrels, turkey, and other game shot at 40-yard and longer ranges. Turkey hunters sometimes use Extra Full or Turkey choke for even denser patterns at long range.

Full Choke

Shot String at Various Distances

Shot String at Various Distances

Steel Shot

Steel shot is slightly lighter than lead shot of the same size—reducing its velocity and distance (range). Also, steel shot is harder than lead, so the individual pellets stay round, keeping the pattern tighter.

- Some hunters use steel shot one or two sizes larger to make up for the difference in weight from lead shot. Others use the same size steel shot, or even smaller steel shot, to get more shot into their patterns. You should pattern your shotgun with various loads of steel shot before hunting waterfowl with it.

- Effective pattern density is the key. Maximum pellet counts spread evenly across a 30-inch circle are best. Full chokes generally produce poor patterns with steel shot.

Topic 8: Using the Correct Ammunition

Match Firearms and Ammunition Correctly

With so many kinds of firearms and types of ammunition, it’s not always easy to match the proper ammunition to your firearm correctly—but getting it right is critical. If you match the wrong ammunition to your gun, you can cause an explosion, injuring or possibly killing yourself and any bystanders.

To match the proper ammunition to your rifle, shotgun, or handgun correctly:

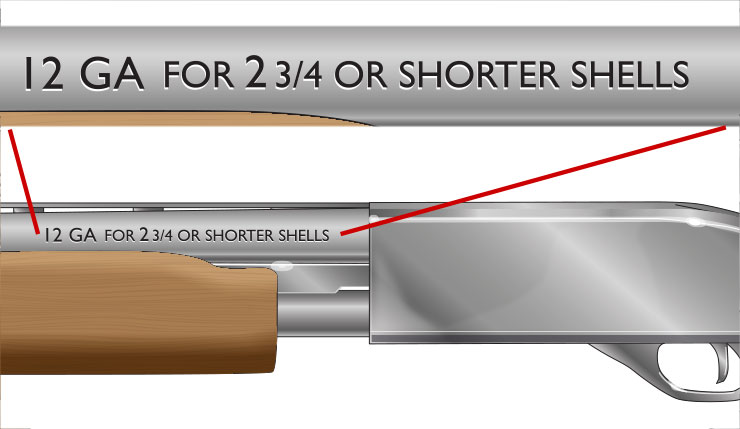

- Read the specific caliber or gauge designations on the side of the barrel. Match that barrel stamp designation exactly. For example, if it says “.270 Winchester,” you cannot use “.270 Weatherby.” Shotgun barrels will give the gauge and the length of the chamber (for example, “12-gauge for 2¾-inch shells” or “20-gauge Magnum for 3-inch shells”).

- Carefully read the information on the lid of the ammunition box and on the head stamp on the ammunition. With shotgun ammunition, always check both the gauge and the shell length, and whether it’s a magnum load, to ensure it matches the data on the barrel.

- Finally, match the proper caliber of cartridge, or gauge and length of shotshell, on the ammunition box and the ammunition head stamp to the barrel stamp before you shoot.

The rear of the shotgun barrel should be marked with the gauge and the length of the chamber.

The barrel stamp of a rifle is usually stamped toward the rear of the barrel.

load: The amount of gunpowder in the cartridge or shotshell together with the weight of the bullet or shot charge

Safety Practices to Help You Avoid Using Wrong Ammunition

Safety practices that will help you avoid using the wrong ammunition are:

- Purchase only the correct ammunition for your firearm. Buy the exact caliber or gauge and length of ammunition for which your rifle, handgun, or shotgun was designed. For example, shotshells must be the correct length for the shotgun. The data stamp on the barrel of the shotgun will identify what length shell can be used. Never use a shell that is longer than this length.

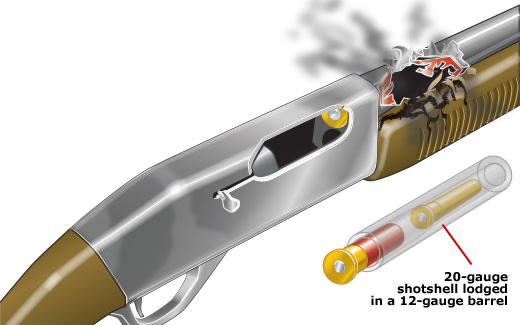

- Carry only the correct ammunition for the firearm you’re using. Never mix ammunition, such as carrying a caliber or gauge your companion uses. A common mistake involves putting a 20-gauge shotshell into a 12-gauge shotgun. The smaller gauge shell will slide through the 12-gauge chamber and partly down the barrel, causing an obstruction. The shooter, especially when excited by the presence of game, then might insert a 12-gauge shotgun shell behind the 20-gauge shell.

- Never use old ammunition. Contact your local law enforcement agency for advice on destroying it.

Important

Reloaded shells may have wrong information or have been improperly reloaded. It’s important to mark reloaded shells clearly. Use only shells or cartridges that you have reloaded yourself or that have been reloaded by a person whom you know is competent.

The Danger of Using Wrong Ammunition

Smaller shotshells (such as 20-gauge shells), if mistakenly fed into a 12-gauge gun, will slip past the chamber and lodge in the barrel, causing serious personal injury or gun damage if a 12-gauge shell is loaded and fired. Some rifle and handgun ammunition also may fit into the wrong gun, creating a dangerous obstruction. The caliber or gauge stamped on the end of the shell must match that which is stamped on the gun barrel. Some barrels are not stamped. Be sure the right ammunition is used in your gun.

Topic 9: A Firearm’s Range

Know Your Firearm’s Range

Knowing your firearm’s “maximum projectile range” is critical to being a safe and responsible hunter. The maximum projectile range tells you at what distances your firearm’s projectile could cause injury or damage to persons, animals, or objects. When hunting, knowing the “effective killing range” lets you immediately assess when a shot will give a clean kill. The effective killing range will always be less than the maximum projectile range. Learning to estimate distances and knowing your firearm’s projectile range and your effective killing range are important parts of hunting.

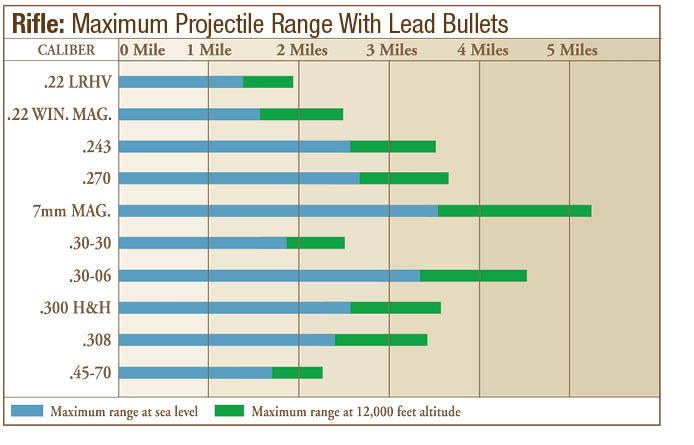

Maximum Projectile Range: Rifle

The following chart shows the maximum projectile range when you use lead bullets in your rifle. Notice how altitude affects this range.

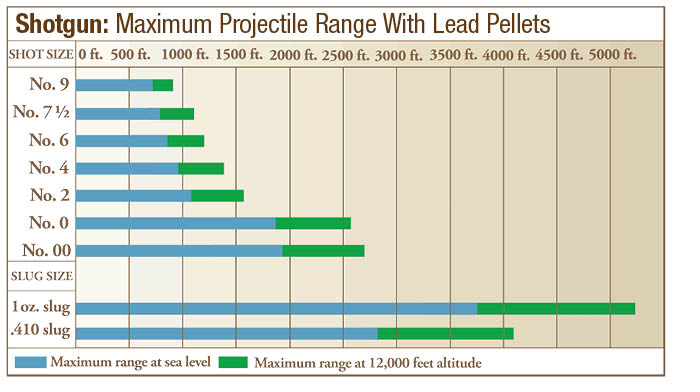

Maximum Projectile Range: Shotgun

The following chart shows the maximum projectile range when you use lead pellets in your shotgun. Notice how altitude affects this range.

Maximum Projectile Range: Handgun

The following chart shows the maximum projectile range when you use lead bullets in your handgun.

Topic 10: Cleaning and Storing Firearms

Firearm Cleaning Basics

Clean your firearms after every use to keep them in top condition. This will help ensure that the action functions safely and properly and the ammunition performs as it should.

- Work on a cleared table or bench. Always give cleaning your full attention. Never clean a firearm while doing something else.

- Follow these basic steps to clean your firearm.

- Point the muzzle in a safe direction, and make sure the gun is unloaded.

- Remove all ammunition from the cleaning bench.

- For the most thorough cleaning, field strip the firearm as directed in the firearm owner’s manual. Then clean each part separately.

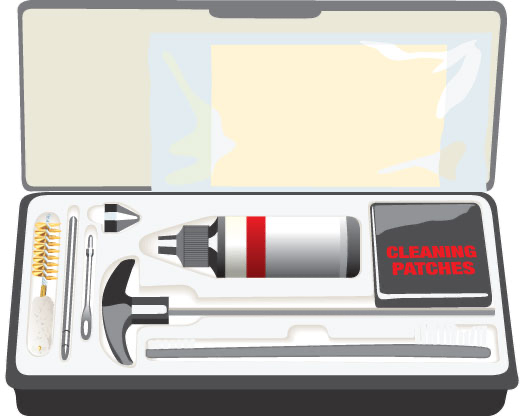

A Cleaning Kit

Every hunter should own a complete cleaning kit. A cleaning kit should include:

- Assorted rod tips—brushes, mop tips, slotted tips, jag tips

- Bore light

- Clean cloths

- Cleaning rods

- Cotton swabs

- Dental mirror

- Gun grease

- Gun oil

- Gunsmith screwdrivers

- Patches appropriate for the caliber or gauge of the firearm

- Pipe cleaners

- Solvent

- Stand to hold the firearm securely in a horizontal position

- Toothbrush

General Cleaning Instructions

Follow the instructions in your cleaning kit.

- Use a cloth and cleaning solvent to remove dirt, gunpowder residue, skin oils, and moisture from the action and all other metal parts of the firearm.

- If possible, clean the barrel from the breech end, using a bore guide and a cleaning rod holding a bore brush or patch wetted with solvent. Pass the brush/patch all the way through the barrel. Repeat several times with fresh patches. You may need a larger brush for the chamber.

- Use a hand brush to clean the crevices where powder residue accumulates.

- Follow with a dry patch, and finish with a lightly oiled patch for the barrel. Use cloth for other parts.

- Apply a coating of gun oil to protect the firearm from rust.

Use a flexible “pull-through” cleaning cable when cleaning firearms with lever or semi-automatic actions to prevent dirt, grime, or debris from being pushed into the action area.

Clean your ammunition by wiping it with a cleaning cloth. If the ammunition is not clean, particles of sand or dirt can scratch the bore.

Use cleaning solvents in a well-ventilated area and only as directed.

If cleaning from the muzzle end, use a muzzle protector so that you don’t damage the rifling near the muzzle.

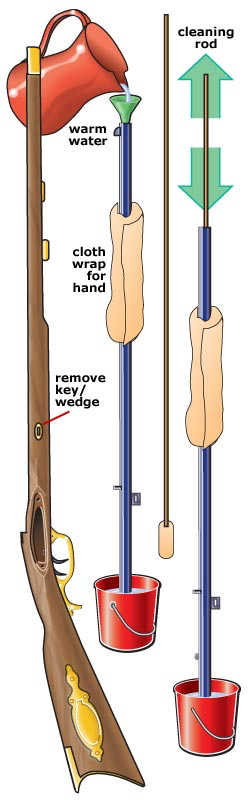

Steps for Cleaning a Firearm

Step 1: Clean barrel and metal parts with good commercial solvent.

Step 2: Bore should be cleaned through breech end where possible.

Step 3: Clean bore until dry patch comes through as clean as possible.

Step 4: Run oily patch through barrel.

Step 5: All metal parts should get light coat of oil.

Step 6: Store in horizontal position, or with muzzle pointing down.

Step 7: After storage, run a clean patch through bore before firing.

Step 8: Remove all excess grease and oil.

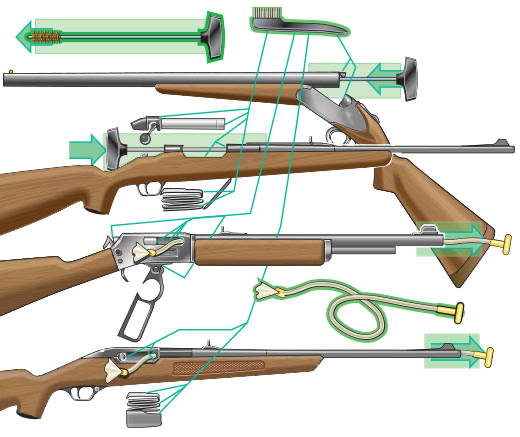

Where to Use a Brush, Cleaning Rod, and Cleaning Cable

These illustrations show where to use a brush and a cleaning rod to clean a gun.

Cleaning of a Rifle

Cleaning of a Handgun

Storing Your Firearm

Firearms must be stored unloaded and in a locked location, separate from ammunition.

- The storage area should be cool, clean, and dry. Storing firearms in closed gun cases or scabbards isn’t recommended because moisture can accumulate.

- Store guns horizontally, or with the muzzle pointing down. When guns are stored upright, gravity pulls gun oil downward into the action, which forms a sticky film. Oil also can drain onto the stock, softening the wood.

- Displaying guns in glass cabinets or wall racks is an invitation to thieves and curious children.

- If guns are stored in an accessible area, such as a closet, put a locking device on each one.

- Ideally, guns should be hidden from view and locked. Storage devices with hidden compartments are available. For the best protection against theft and fire damage, purchase a safe.

Storing Ammunition

Follow these guidelines for storing ammunition.

- Store ammunition, reloading supplies, and firearms in separate locked compartments.

- Keep all ammunition away from flammables.

- Store ammunition in a cool, dry place to prevent corrosion. Corroded ammunition can cause jamming, misfires, and other safety problems.

Unit 3: Basic Shooting Skills

Topic 1: Good Marksmanship and Accuracy

Fundamentals of Good Marksmanship

A fair amount of knowledge, skill, and experience is required to become a successful hunter. One of the essential skills is good marksmanship, which is accurately and consistently hitting the target where planned. When hunting, accuracy is critical for a clean kill. Good marksmanship is built on three fundamentals:

- Proper sight adjustment or patterning

- Proper shooting technique

- Practice

Selecting the Proper Firearm and Ammunition

- When choosing a firearm for hunting, make sure you meet any minimum legal requirements for caliber, gauge, or the amount of energy produced by the projectile. When hunting, your firearm should:

- Be powerful enough to kill the game quickly and effectively and…

- Fit you properly and…

- Have the correct amount of recoil, usually moderate, so that you will practice more often and shoot more proficiently.

- The ammunition you select for hunting depends on the type of game you plan to hunt. Most manufacturers recommend specific ammunition for each species.

- When hunting with a shotgun, also be sure to select the proper choke and ammunition combination.

Determining Accuracy Limits

After selecting your firearm, you should practice with it before you go hunting. Ethical hunters know their personal accuracy and limit their shots accordingly.

- Rifles: Use an 8-inch paper plate as the standard target to establish deer hunting accuracy. An 8-inch target is about the same size as the vital area of a deer. Before hunting, practice until you are confident you can hit the required target at the distances and from the shooting positions you expect to use in the field. When hunting, limit your shots to your most accurate range.

- Shotguns: Pattern your shotgun, and then practice hitting targets at the distances you expect to be from game you shoot. This will develop proficiency with the chosen firearm and help to ensure an ethical, clean, quick kill.

Protecting Your Vision and Hearing

Shooting a firearm can cause immediate and permanent hearing loss and can damage your vision.

- Shooting a firearm creates a loud noise. To protect your hearing, always wear properly fitting ear protection.

- For target practice, use an earplug or earmuff (or both) with a high Noise Reduction Rating (NRR).

- When hunting, use electronic or non-linear devices that allow normal or even enhanced hearing but block damaging levels of sound.

- For more information, visit the National Hearing Conservation Association website.

- Not only does shooting a firearm send the projectile(s) downrange, but it also discharges small particles from the projectile, burning gas, and other residue. Also a shell could rupture or your firearm could malfunction.

- When shooting, always wear suitable eye protection, such as shooting glasses with high-impact lenses, to protect your eyes.

- Wear eye protection also whenever disassembling or cleaning a firearm.

Topic 2: Rifle Firing

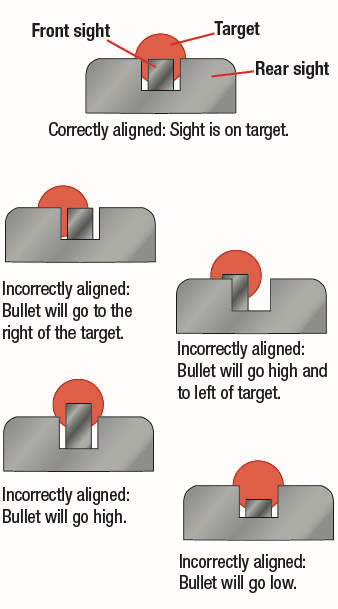

Sight Alignment

Sight alignment is the process of lining up rear and front sights. The sight picture is the image you see when the sights are aligned correctly with the target. To ensure that the bullet will travel to the target in your sight, it’s necessary to sight-in your rifle or handgun.

With an open sight, you line up the target with the blade or bead of the front sight within the notch of the rear sight.

With an aperture sight, you line up the target so that the front sight is within the rear peephole.

With a telescopic sight with a crosshair reticle, you line up the target with the crosshairs of the sight.

With a telescopic sight with a dot reticle, you line up the target with the dot of the sight. The dot must be centered.

Aligning an Open Sight

Determining Your Dominant or Master Eye

Just as you have a dominant hand, you also have a dominant eye.

- You need to aim with the dominant—or master—eye for the most accurate shooting. Usually your dominant eye is the same as your dominant hand, but not always. You should determine which is your dominant eye before you sight-in your rifle or handgun.

- To determine your dominant eye:

- Form a triangular opening with your thumbs and forefingers.

- Stretch your arms out in front of you.

- Focus on a distant object while looking through the triangular opening and keeping both eyes open.

- Bring your hands slowly to your face, keeping sight of the object through the opening; the opening will come to your dominant eye naturally.

- If you’re not sure, close one eye at a time. The weak eye will see the back of your hand; the strong one will be focused on the object in the triangle.

Important

Good vision is the foundation for good shooting and hunting safety. Have your eyes examined on a regular basis.

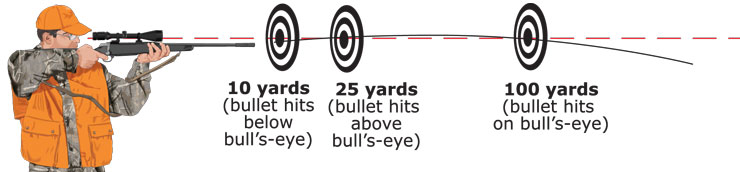

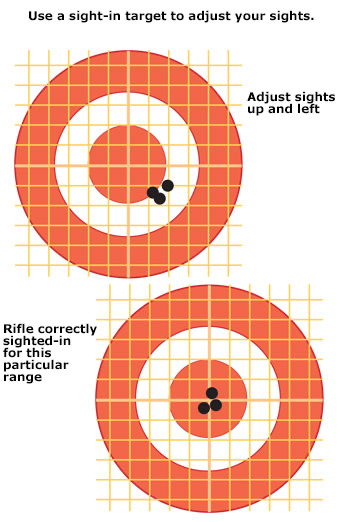

Sighting-In a Rifle

Rifle bullets don’t travel in a straight line. They travel in an arc, formed by the pull of gravity.

- “Sighting-in” is a process of adjusting the sights to hit a target at a specific range. Deer hunters, for example, often sight-in their rifles to hit the bull’s-eye at 100 yards.

- All rifles should be sighted-in before every hunt using the ammunition you plan to use, especially rifles with peep or telescopic sights. Guns you sighted-in prior to your last outing could have been knocked out of alignment by a single jolt. That misalignment could mean the difference between a successful hunt and a disappointing experience.

- Other than ensuring accurate shots, sighting-in a rifle has other advantages:

- Forces you to practice

- Makes accurate shooting possible

- Helps identify problems with your firing technique

- Helps determine the farthest range at which you can hit your target

- Improves safety by helping you know where your rifle will fire

- Builds confidence in your shooting ability

Optional Sighting-In Techniques

Use bore or collimator sighting-in initially to line up the rifle on the paper target. However, these techniques alone are not sufficient to sight-in a rifle. You must make final adjustments by firing the rifle with the same ammunition you plan to use in the field.

- Bore sighting-in with bolt-action rifles: Remove the bolt, brace the firearm on sandbags, and look directly through the bore. Correct the rifle’s position until you see the bull’s-eye in the center of the bore. Adjust the sights to give you a good sight picture.

- Collimator sighting-in for rifles without bolt actions: A collimator slips into the muzzle end of the barrel and allows you to adjust the sights, much like bore sighting-in.

Important

You must sight-in your rifle with the ammunition you plan to use. Be sure you sight-in and practice firing your rifle before you go hunting.

Sighting-In Procedure

Fire your rifle from a solid bench rest with the forestock resting on a pad or a sandbag. Don’t rest the gun on its barrel—it will shoot higher than normal. Ideally, use an adjustable shooting tripod with sandbags. A spotting scope is also useful.

Sight-in instructions are printed on some targets available from retail outlets or manufacturers. The sighting-in process for most centerfire rifles begins at 25 yards and then should be repeated at 100 yards. The basic steps involve firing at least three shots carefully and consistently at a target. If the bullets form a relatively small group of holes on the target, but not where you were aiming, the sights will have to be adjusted.

Adjusting Your Sight

When adjusting peep or telescopic sights, the rear sights or dials are adjusted by a certain number of minutes-of-angle, or “clicks,” in a certain direction. Read the sight’s instruction manual to see how much each click changes the sight at 100 yards.

The rear sight is moved in the same direction you want your shot to move on the target. Moving shots from side to side is “adjusting for windage.” Moving shots up or down is “adjusting for elevation.”

Specific instructions about trajectory and what fractions or inches you should be above the bull’s-eye at 25, 50, or 100 yards are usually included on sight-in targets. You also might consult a ballistics chart or get help from an experienced shooter.

MOA

The standard measurement unit of shooting accuracy; one minute-of-angle (MOA) is 1/60 of one degree, or approximately one inch, at 100 yards

Rifle-Firing Techniques

Using correct firing techniques will help you steady the rifle for the most accurate shooting. Bear in mind that these are only the basics. Further study will help you understand other factors that can affect your accuracy, such as wind, heat, and parallax.

- Shooting From a Rest: When shooting in the field, the safest and most accurate shots are taken from a rest—a log, large rock, or other stable object. Don’t rest the barrel directly on a hard surface, or the rifle will fire higher than normal—put some padding, such as a hat or a jacket, under the rifle.

- Breathing: Your breathing can move the rifle just enough to throw off your shot.

- When you’re ready to fire, draw a deep breath, and exhale about half of it.

- Then hold your breath as you squeeze the trigger.

- Bear in mind that if you hold your breath too long, your heart beats faster, which increases your pulse and causes the rifle to move. If you notice this happening, take another breath and start over.

- At times the excitement of spotting game will make it more difficult to control your breathing. Try to relax and follow the correct procedure.

- Trigger Squeeze: Jerking the trigger or abruptly clenching the trigger hand can move the gun enough to cause a miss.

- To squeeze the trigger without jarring the gun, simply apply slow, steady pressure until the gun fires.

- Practice makes breath control and proper trigger squeeze habitual.

- Follow Through: After the bullet fires, it’s important to continue the squeeze or follow through. That prevents you from jerking the gun before the bullet has left the barrel.

Four Fundamentals for an Accurate Rifle Shot

- Aim carefully, aligning your sights.

- Take a deep breath, and then release about half of it.

- Squeeze the trigger slowly.

- Follow through.

parallax: Optical bending of telescopic crosshairs in relation to the target

Firing Positions: Prone

There are four standard rifle-firing positions: prone, standing, sitting, and kneeling.

Prone

The prone position is the steadiest of the four positions. Because it’s the easiest to hold, it’s the best position for mastering the fundamentals of firing—aiming, breath control, trigger squeeze, and follow through.

Firing Positions: Standing

There are four standard rifle-firing positions: prone, standing, sitting, and kneeling.

Standing

With neither arm supported, this is the most difficult position for firing an accurate shot. Rather than trying to hold the barrel steady, which is impossible, try to keep movement of the barrel to as small an area as possible. Smooth, natural motion will produce the best shot

Firing Positions: Sitting

There are four standard rifle-firing positions: prone, standing, sitting, and kneeling.

Sitting

Both arms are supported by your legs. Next to the prone position, this is the steadiest position.

Firing Positions: Kneeling

There are four standard rifle-firing positions: prone, standing, sitting, and kneeling.

Kneeling

With only one arm braced, the kneeling position is less steady than the prone and sitting positions.

Topic 3: Shotgun Shooting

Shooting a Shotgun vs. a Rifle

Shotgun

- Point a shotgun.

- Focus your eye on the target.

- Pull the trigger.

Rifle

- Aim a rifle.

- Focus your eye on the crosshairs or front sight.

- Squeeze the trigger.

Hunter’s Tip

- Point a shotgun. Pull the trigger.

- Aim a rifle. Squeeze the trigger.

Choosing the Proper Choke

As with firing a rifle, good shotgun marksmanship begins with proper preparation, which includes adjusting your gun and ammunition for maximum performance and mastering shotgun techniques. You also must choose the proper choke.

- A choke allows you to fine-tune your shotgun for the type of game you’re hunting. Built-in or attached to the muzzle end of the barrel, the choke is a constriction that controls the shot string, thus affecting pellet density at various distances.

- The tighter the constriction, the greater the distance that the cluster of pellets stays together. The looser the constriction, the faster the shot pattern spreads.

- Here are the four most common chokes, ranging from most open to tightest.

- Cylinder (unchoked)

- Improved Cylinder

- Modified

- Full

Cylinder Choke

Improved Cylinder Choke

Modified Choke

Full Choke

Matching Choke to Your Quarry

Here are some examples for matching the choke to the quarry. Someone hunting small, fast, close birds would generally use an Improved Cylinder or Modified choke, which creates a broad shot pattern that spreads quickly at close ranges. Conversely, someone hunting a larger, less mobile bird that is usually farther away, such as a turkey, would select a Full choke, which concentrates the shot in a smaller area. Pellet size also varies based on the size of the game.

The chart below suggests choke selections for a variety of game. It is intended only as a guide—choice of choke may vary depending on ammunition, target distance, and hunting conditions. Always pattern your shotgun for the quarry you are hunting and the ammunition you are using.

| Quarry | Commonly Used Choke (based on typical distance from quarry) |

|---|---|

| Goose | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Duck | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Turkey | Full or Extra Full |

| Pheasant | Improved Cylinder, Modified, or Full |

| Grouse | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Woodcock, rail, or snipe | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Dove | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Quail | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Rabbit | Improved Cylinder or Modified |

| Squirrel | Modified or Full |

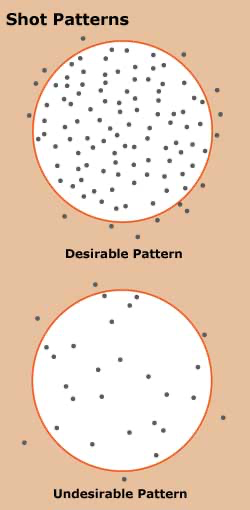

Patterning Your Shotgun

No two shotguns will shoot identical pellet patterns. In some cases, the pattern will be off-center. In other instances, there may be gaps in the pattern. In addition to the firing characteristics of the gun, the gun’s choke, the brand of shotshell, the shot size, and the type of shot also affect the pattern. In order to select ammunition that provides the best performance, it’s necessary to “pattern” your shotgun.

Important

Shots at game birds in flight should be limited to your “maximum effective range.” This is the distance at which you can hit the target consistently. Shooting beyond this distance leads to an increased number of birds wounded and lost. Also, firing at game too close may destroy the meat.

The Patterning Procedure

Patterning can be done with simple, homemade targets—sheets of blank paper about 4 x 4 feet in size. A commercial target with a bull’s-eye also can be used, but the bull’s-eye is used only to aim at—it is not used in steps 2–4 below. To pattern your shotgun, follow these steps:

- Fire one shot at the center of the target (or bull’s-eye) from the distance that you expect to be from your quarry (for example, 35 yards if hunting game birds). Repeat this two more times, each time with a new sheet of target paper.

- On each of the three targets, draw a 30-inch circle around the densest part of the shot pattern. (This is not necessarily the center of the paper.)

- On each of the three targets, count the number of pellet holes that fall within the 30-inch circle, marking them with the marker as you count each one.

- Calculate the percentage of the load that is expected to land in a 30-inch circle at the distance that you expect to be from your quarry.

a. Average the pellet counts within the 30-inch circles (add the three counts from the previous step, and divide the sum by three).

b. Then divide the average pellet count by the number of pellets in the load for the ammunition you are using, and multiply this result by 100.

When Is Your Shot Patterning Correct?

The pattern of pellets within a 30-inch circle should be of a proper, even density to ensure a clean kill. The pattern should contain a sufficient percentage of the load, which should be at least 55% to 60%.

Continue this process, trying different choke and load combinations, until you get an even pattern density with a sufficient percentage of the load within a 30-inch circle while shooting from the distance that you expect to be from your quarry.

Shotgun-Shooting Stance

Unlike rifle firing, quick reflexes and flexibility are essential for effective shotgun shooting.

- Proper shotgun techniques will help you develop the rapid, fluid response you need to hit your target.

- A shotgun is almost always shot at a moving target from a standing position. You must be able to swing freely over a wide arc and maintain control. That requires a relaxed, balanced stance.

- Stand with your feet spread about shoulder-width apart and your knees bent slightly so that you are balanced perfectly. Bring your left foot slightly forward (if you’re a right-handed shooter), and lean your body in the same direction. The position of the feet is important. The toes of your forward foot should point at about 45 degrees toward the target. Take the time to place your feet properly, even for a quick shot.

- Keeping your knees slightly bent makes it easier to swing with a moving target. The bent leg to the rear supports the movements of your hips, allowing you to swing smoothly.

Shouldering, Pointing, and Pulling the Trigger of a Shotgun

Shouldering the Shotgun

- When you bring the shotgun to your shoulder, the stock should be brought to your cheek first and then back to your shoulder.

- A common error is lowering the head and cheek to the stock, instead of bringing the stock all the way up to the cheek. When done properly, with your head naturally erect, the gun butt always should come to the same spot on your shoulder.

Pointing a Shotgun

- Because targets usually appear suddenly and move quickly, there’s no time to “aim” a shotgun. It’s designed to be pointed, with the eye sighting along the top of the barrel or rib.

- The sight is usually a bead on the front of the gun. Your eye must be in line with the barrel, so it’s important to position your head properly on the stock.

- When you bring the gun to your face, the stock should fit snugly against your cheek with your eye on that side above the centerline of the gun. If you can’t assume that position comfortably, you may need to adjust the “gun fit.”

Pulling the Trigger

- Unlike rifle firing, quick trigger action is important when hunting with a shotgun. To fire, quickly slap the trigger with a firm motion, keeping a firm grip on the shotgun while pulling the stock rearward.

- Because the trigger is pulled quickly and the body and gun are typically in motion, breath control isn’t necessary.

- Continue the shotgun’s swing as you pull the trigger. Stopping the swing as you shoot will cause you to hit behind a moving target.

Leading the Target: Swing-Through Method

The two most common methods of leading targets at long distances are swing-through and sustained lead.

- Swing-through is the best technique for the beginning student.

- Point your shotgun at a moving target and swing with it. Increase the speed of the gun so that the muzzle passes the target, and then fire. In other words, literally “swing through” the target and fire at a blank space in front of the target.

Leading the Target: Sustained Lead

The two most common methods of leading targets at long distances are swing-through and sustained lead.

- The sustained lead method is a little more challenging because it requires more experience.

- You estimate the length of the lead necessary to hit the target, and maintain that lead as you swing with the target, fire, and continue the swing.

Snap-Shooting

Snap-shooting is a technique to use if you must make a quick shot and the target is straight ahead at close range. You simply raise the shotgun, and point where you think the target will be when the shot arrives.

Topic 4: Handgun Shooting

Handgun Loading and Handling

Hunting with handguns has grown in popularity in recent years. Many of the fundamentals of rifle firing also apply to shooting handguns.

- Single-action revolvers typically load through a gate on the right side of the frame. To rotate the cylinder, pull the hammer back to half-cock. For a safer carry in the holster or hand, leave an empty chamber in front of the hammer.

- Double-action revolvers have cylinders that fall downward, exposing all chambers for loading.

- Semi-automatics usually fire rounds stored in a magazine that is inserted in the grip or handle.

Handgun-Shooting Position and Grip

Body position and grip are vital to hitting the target. The hand position on the grip of a pistol is especially critical. Although the grip configuration of the revolver and semi-automatic are different, the gripping procedure is the same.

- Hold the handgun high on the grip so that the recoil is directed back to the hand and arm in a straight line. This allows better repeat shots and more accurate shooting.

- Use a two-handed hold whenever possible, applying pressure from front to rear.

When hunting, use a tree trunk, steady limb, or other stable object as a rest. Placing some padding, such as a hat or a jacket, on top of a hard rest helps with your aim.

Handgun Sight Alignment and Aiming

Sight Alignment

Sight alignment, which is important in rifle firing, is even more important in pistol shooting because of the shorter distance between the sights.

- Typically, handgun sights consist of a square rear notch sight and a heavy square front blade sight. This arrangement is easy to align.

- Most handguns are initially sighted-in at 50 feet.

Aiming

- At the shooting range, many handgunners use a sight picture that places the bull’s-eye on the top of the front sight, rather than placing it in the sights over the center of the target. However, hunters should hold the alignment directly over the vital area.

- Scopes with long eye relief have become popular with handgunners and offer exact sighting for hunters. Scopes may take longer to align on a target than open sights, but they’re usually more accurate.

Handgun-Shooting Techniques

The pistol-shooting fundamentals of breath control, trigger squeeze, and follow through are almost identical to those in rifle firing. There are, however, some important differences to remember.

- The first joint of the finger should take up trigger pressure, not the tip, as is often done with rifles.

- When a revolver is fired, powder flashing at the front of the cylinder can cause burns. Be sure to keep your fingers away from the front of the trigger area.

- The slide and hammer of a semi-automatic gun can deliver a bruising blow when held too close to the body. All handguns should be fired at arm’s length.

Important

When using a handgun:

- Use a good holster with a safety strap.

- Draw a handgun only when you see game.

- Cock your gun only when ready to shoot.

- Keep your finger outside the trigger guard until ready to shoot.

Unit 4: Basic Hunting Skills

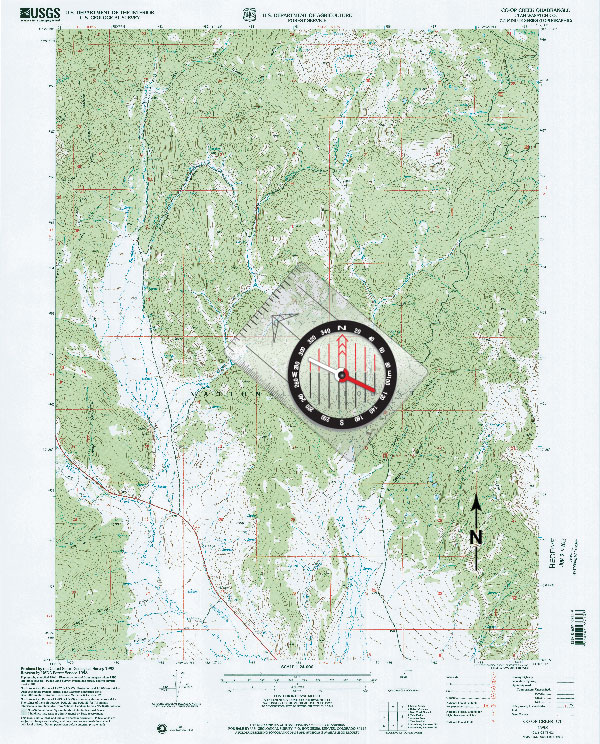

Topic 1: Planning and Preparation

Steps You Should Take to Prepare for a Hunt

A successful hunt begins with careful planning and preparation. The process usually requires more time than the hunt itself. Here are some steps you should take to prepare for a hunt.

- Educate yourself about the game you’ll be hunting and its environment.

- Obtain the most current state regulations.

- Buy appropriate clothing and gear for the environment.

- Secure lease arrangements and permits (dogs and horses may require - a veterinarian’s certificate or a current vaccination record).

- Visit the site in the off-season to prepare blinds and cabin facilities.

- Sight-in rifles, handguns, and bows; pattern shotguns.

- Sharpen your skills at the shooting range.

- Pack extra firearms, scopes, bowstrings, etc.

Know Your Quarry

Of all the steps of preparation, educating yourself about the game you’re hunting is one of the most critical. Understanding your quarry will increase your success and add to the enjoyment of the experience as well.

- In many cases, knowing your quarry is also necessary to ensure that you’re taking legal game. For example, you may need to determine the sex of game birds on sight or quickly recognize protected species as they move into firing range. If you hunt in a region where white-tailed and mule deer occupy the same area, you’ll need to know how to identify both.

- There are many ways that wild animals are classified, but hunters are concerned with four basic categories.

- Large Mammals: Big game, such as deer, elk, and bear

- Small Mammals: Small game, such as rabbits, squirrels, and raccoons

- Upland Birds: Turkey, grouse, quail, and dove

- Waterfowl: Ducks and geese

Important

It is critical that you educate yourself about your quarry when preparing to hunt. Understanding game species will add to your enjoyment and increase your chances of success as well.

Understand Animal Characteristics

Whatever you’re hunting, a basic understanding of an animal’s characteristics will help you develop an effective strategy for identifying and tracking it.

- Animals can be identified by four basic characteristics.

- Distinctive Markings: The black cheek patch on male pronghorns; the “flags” of the white-tailed deer; the face pattern on a gray fox; the green head on a mallard drake; the red, white, and blue on the head of a male turkey

- Sounds: The wild call of the sandhill crane, the familiar honk of the goose, the gobble of a strutting “tom,” the grunt of the deer, the howl of the coyote

- Movement: The bounce of mule deer, the strut of a tom turkey, the fast or slow wing beats of some waterfowl, the zigzag in-flight pattern of the common snipe when flushed

- Group Behavior: Flock patterns, such as the familiar V shape of certain migratory birds; various types of herd behavior

- Further study will help you learn other ways to identify and understand your quarry, including signs the animal leaves, camouflage capability, and behavior.

Topic 2: Hunting Strategies

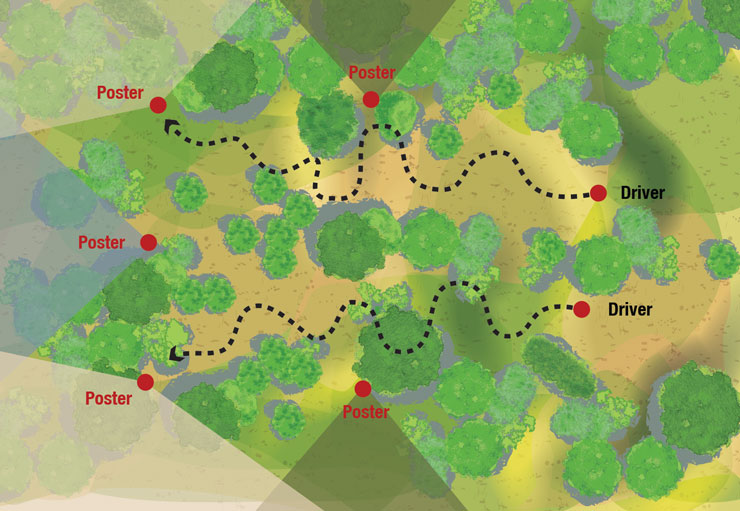

Introduction to Hunting Strategies

Hunting techniques are skills honed through education and experience. Ideally, beginners should seek the guidance of experienced hunters on their initial hunts

Still Hunting

As the name implies, still hunting is walking stealthily through an animal’s habitat, stopping frequently—sometimes for long periods—to scan and listen for game. Typically, big-game hunters use this method in unfamiliar terrain or where stands are impractical or forbidden.